I am very pleased to announce the publication of a review paper in the Journal of Arachnology (check out the full pdf here) about the fascinating uses of silk during spider sexual interactions coauthored with Alissa Anderson and my supervisor Maydianne Andrade. This paper has been several years in the making, and some of my very first blog posts were based on the research I did when I first started writing it back in 2013 as part of a reading course for my MSc degree.

Pisaurina mira (a nursery web spider in the family Pisauridae), one of the many diverse species featured in our paper, and the focus of my coauthor Alissa’s PhD research (photo: Sean McCann).

Overview

In this paper we describe the many weird and wonderful ways that male spiders use silk during courtship and mating. Little experimental work has been done to determine the function male silk in sexual interactions, but the available research suggests that in general silk use improves the male’s chances of mating with a particular female or reducing the risk that she will mate with other males. There is also mounting evidence that silk-bound sex pheromones are commonly produced by male spiders (though much less well studied than female silk pheromones), which may help to explain the importance of silk production during sexual interactions in many species. In the paper, we divide male silk use into three categories, briefly summarized below.

- Silk deposition on the female’s web or other silk structures

Figure 2 from the paper. Examples of silk deposition onto females’ webs during courtship. (a) Araneus diadematus (Araneidae) male and female hanging from the male’s mating thread, attached to the periphery of the female’s web (photo: Maria Hiles). (b) Web reduction with silk addition by a Latrodectus hesperus (Theridiidae) male. The male has dismantled part of the capture web (which would have filled the lower half of the photograph before he began web reduction behavior) and is wrapping it with his own silk (photo: Sean McCann).

The most common and widespread form of silk use during sexual interactions across spiders is simply the deposition of silk on the female’s web or the silk surrounding her burrow entrance. More elaborate use of silk includes the installation of silk mating threads or webs on which courtship and copulation take place and web reduction, which can result in extreme modification of web architecture. The few experimental studies of this kind of silk use indicate that it is involved with preventing females from mating with other males, as in black widows. However, it is likely that mating threads and webs generally function to improve male mating success by improving transmission of their vibratory courtship signals and/or to reduce the likelihood of sexual cannibalism.

- Silk bondage: the bridal veil

Figure 3 from the paper. Examples of silk ‘bridal veils’ applied to females’ legs and bodies during courtship. (a) Nephila pilipes (Araneidae) male depositing silk onto the female’s carapace, legs, and abdomen (photo: Shichang Zhang). (b) Xysticus cristatus (Thomisidae) female with silk on her forelegs and abdomen as she feeds on a prey item—note that the male is underneath her abdomen (photo: Ed Niewenhuys). (c) Latrodectus hesperus (‘‘texanus’’ morph, formerly Latrodectus mactans texanus; Theridiidae) male depositing silk onto the female’s legs (photo: Sean McCann). (d) Pisaurina mira (Pisauridae) male wrapping a female’s legs with silk prior to sperm transfer (Photo: Alissa Anderson).

The “bridal veil” (which I’ve previously written about in detail here) describes the silk some male spiders wrap around females prior to copulation. Arachnologists have debated the function of this behaviour for many years but it has been generally assumed to prevent sexual cannibalism. In some species like the nursery web spider Pisaurina mira, the silk wrapping physically restrains the female, giving the male time to escape while she struggles free of her bonds. In the orb-weaver Nephila pilipes, on the other hand, tactile cues and chemicals on the silk have been implicated in reducing the female’s aggressive tendencies. In both species, males that wrap females with silk are able to transfer more sperm to females, improving their mating success. Bridal veils are used by males from at least 13 families of spiders, including both web builders and wanderers, and there is still much to learn about the function of this fascinating behaviour across the diverse species that use it. In one species of wolf spider, the female even eats the silk of the veil after mating, which brings us to the third category of male silk use.

- Silk wrapped nuptial gifts, or the gift of silk itself

Figure 4 from the paper. Examples of silk-wrapped nuptial gifts. (a) Female (right) Pisaura mirabilis (Pisauridae) accepts a silk-wrapped gift from a male (photo: Alan Lau). (b) A male (right) Metellina segmentata (Tetragnathidae) has wrapped a rival male in silk as a nuptial gift for the female (photo: Conall McCaughey).

In two families of spider, the nursery web spiders (Pisauridae) and their close relatives the longlegged water spiders (Trechaleidae) males present females with silk wrapped prey items called nuptial gifts (which I previously wrote about here). Sometimes, though, the silk package actually contains non-food items like rocks or plant material. The silk itself seems to be the important thing for getting the female to accept the gift and grasp it in her jaws, keeping her busy (and the male safe) during copulation. Both visual signals associated with the colour of the silk and chemicals on the silk may be important ways that gift-giving males communicate their quality and persuade females to mate with them, not to mention potentially deceiving them into accepting worthless gifts.

In other spiders gift-giving is less ritualized or happens only some of the time, like in the longjawed orbweaver Metellina segmentata. Males of this species often compete on the female’s web, and sometimes one of them will kill his rival, wrap him up with silk, and present him to the female. As with the habitual gift-givers discussed above, mating with the female while she is busy feeding on her erstwhile suitor likely decreases the male’s chance of becoming dinner. In still other spiders, the silk itself constitutes the gift, rather than the wrapping. In the ray spider Theridiosoma gemmosum, the male feeds the female silk directly from his spinnerets during courtship and copulation. This silk gift provides the female with nutrients (these spiders can recycle silk proteins). Finally, silk-lined burrows are considered gifts in the sex-role reversed wolf spiders Allocosa senex and A. alticeps. In these species, males dig deep silk-lined burrows to which they attract females with a pheromone. Mating takes place inside the burrow, and afterward the male helps the female to seal herself inside the burrow where she lays and broods her egg sac. The energy and silk that go into producing the burrow are a considerable investment for the male, and directly benefit the female and his offspring by providing a safe refuge.

The big picture

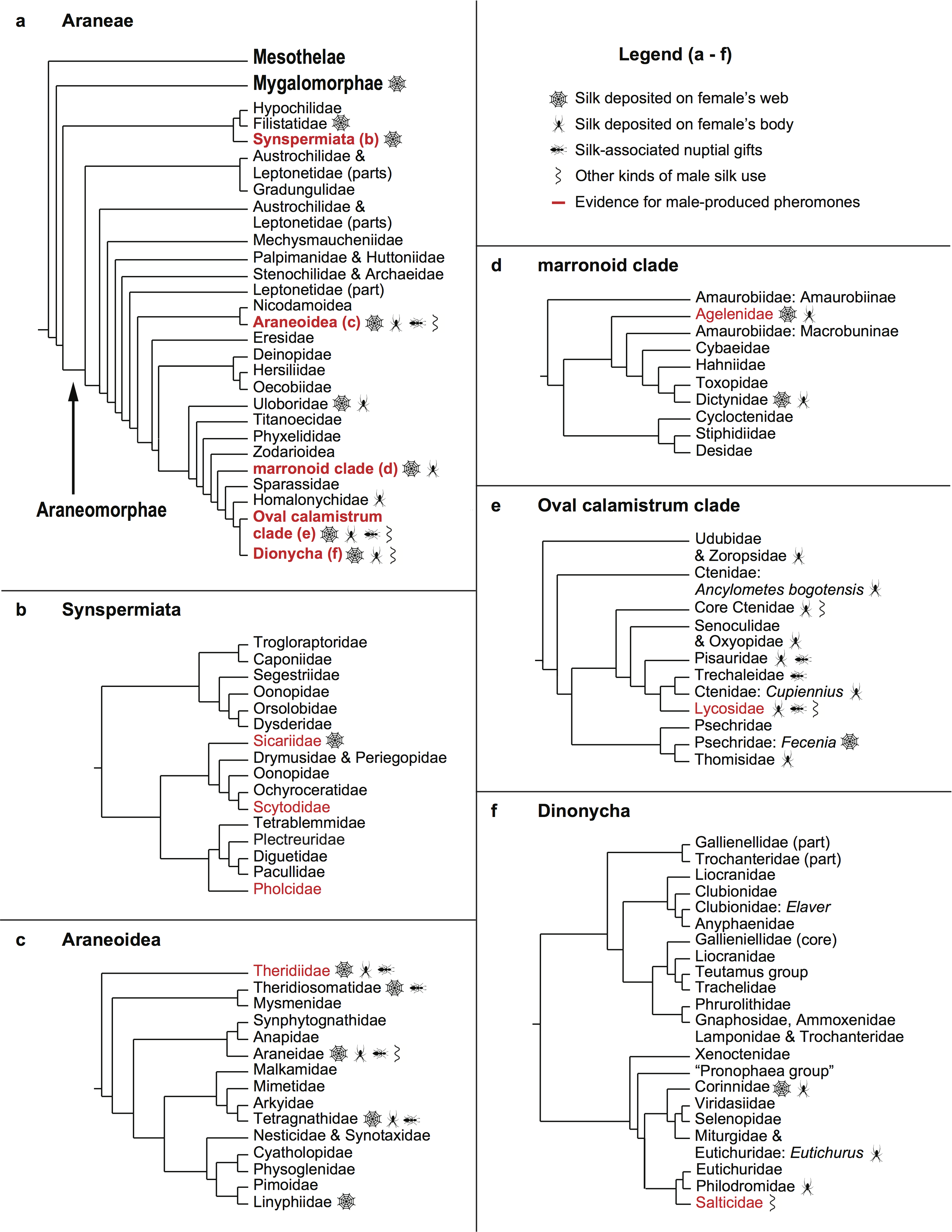

Silk use during courtship occurs in diverse species all across the spider tree of life, and provides myriad opportunities for future research. In the figure below, many families are not highlighted, but this is as likely to represent lack of knowledge about their courtship behaviour (or even anything about their natural history) as lack of silk use, and I hope that this paper will inspire other arachnologists to investigate mating behaviour, silk use, and the potential for male pheromone production in some of these little studied spiders. There are undoubtedly many exciting new discoveries to be made and I look forward to reading about them and perhaps making some myself in the future.

Figure 1.—Cladograms illustrating relationships between araneomorph spider families (based on Wheeler et al. 2016) and the occurrence of male silk and pheromone use. Note that in the Mygalomorphae (families not shown on the figure) there are records of male silk deposition on the female’s web or silk for species in the following three families: Dipluridae, Porrhothelidae, and Theraphosidae.

Full citation of the paper: