I am very happy to share the publication of a new paper reporting research led by my fantastic colleague Lenka Sentenska and coauthored by Pierick Mouginot and Maydianne Andrade, in the journal Behavioral Ecology.

Brown widow spiders (Latrodectus geometricus), like their relatives the Australian redbacks (L. hasselti), are sexually cannibalistic. This is not the situation most people imagine when they hear “black widow,” however, in which the female devours the male after mating. In redbacks and brown widows, sexual cannibalism is better thought of as male self-sacrifice. The diminutive male somersaults during copulation and puts his abdomen in front of the female’s mouthparts, literally offering himself to her and continuing to transfer sperm as she begins to feed on him.

A copulating Australian redback spider pair. The much smaller male has somersaulted, presenting his abdomen to the female so that she can begin feeding on him. Photo: Sean McCann.

At first glance, this doesn’t seem like a particularly good outcome for the male. Although he is able to pass on his genetic material before his death (win!), he will be unable to mate with additional females and increase the total number of offspring he fathers. Recently, a group of colleagues discovered that male redbacks and brown widows can take a shortcut that allows them to survive mating. It turns out that just before their moult to maturity, immature females have fully developed reproductive organs ready to go under the cuticle that they are preparing to shed. This means that a male can bite through the cuticle and successfully copulate with a subadult female, and she will retain the sperm through her moult, and then go on to lay fertilized eggs once she is an adult.

This immature mating tactic has several major benefits for the male: he barely has to spend any time or energy courting the female (usually males court adult females for hours), males mating with subadults are more likely to copulate twice (thus depositing sperm in both of the female’s paired sperm storage organs), and subadult matings do not end in ritual cannibalism! On top of all that, females mated as subadults produce just as many offspring as those mated as adults. Given all this, you might expect that a male brown widow with a choice between an adult and a subadult female mating partner would choose the safer option: the subadult.

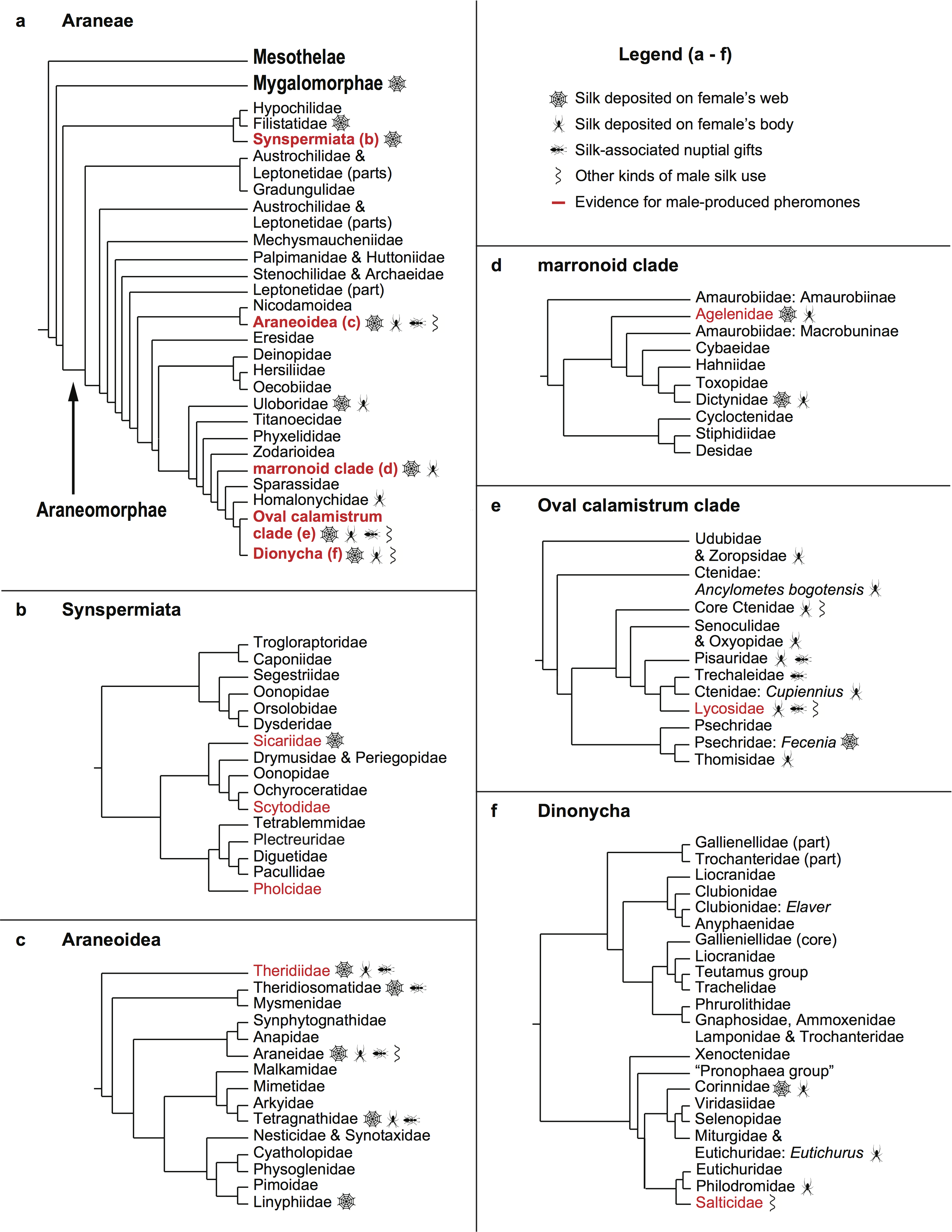

Previous studies (including this one by my colleague Dr. Sentenska) have tested this idea and found that when given a choice, brown widow males preferentially approach adults over subadults. This could just be because subadults are more difficult to detect from a distance; once they mature, adult female widow spiders produce a silk-bound sex pheromone that advertises their location and receptivity to males, and as far as we know, subadults do not produce such airborne signals. In this study, we wanted to see if males would make the same choices based on direct contact with silk (which may contain chemical information that allows males to discriminate between subadults and adults). We also wanted to find out what is driving the reduced courtship and copulatory cannibalism when males mate with subadult females—are courtship behaviours triggered by the sex pheromones on adult females’ webs, or do males adjust their behaviours depending on the kind of female they are attempting to mate, regardless of chemical cues on her web?

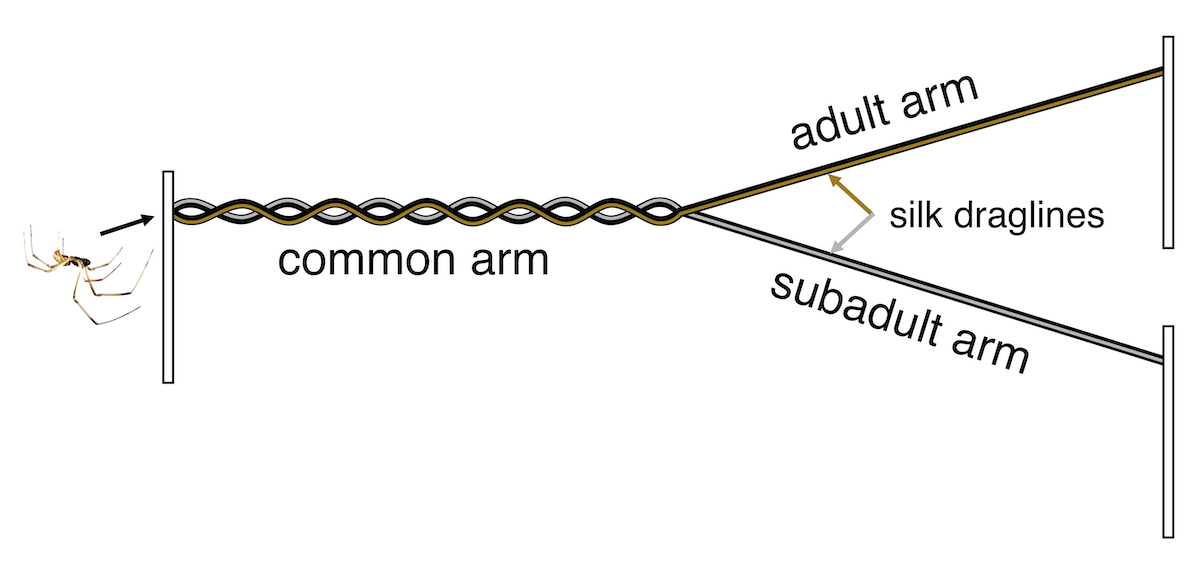

To answer these questions, we ran two experiments. First, we asked males if they preferred silk produced by adult or subadult female’s in a two-choice Y-maze. When the male entered the maze (via the common arm in the figure below) he would be walking on both kinds of silk, and then at the intersection of the Y he could choose to follow the adult or subadult silk trail. Once he got to the end of that arm, he could turn around and go investigate the other option, or continue searching on the first arm he chose. We found that initially, males were equally likely to choose each of the two arms of the Y-maze (not displaying a preference for either kind of silk), but that they spent more time on the adult silk. This reinforces the idea that males prefer adult females to subadult females based on silk-bound chemical cues (which spiders detect with hairs on their legs and mouthparts).

The y-maze setup for testing male brown widows’ responses to contact with dragline silk produced by adult or subadult females.

Next, we ran a web-swap experiment where we placed adult and subadult females on webs built by different individuals who were either the same stage or opposite stage, resulting in four combinations: subadults on subadult webs, subadults on adult webs, adults on subadult webs, and adults on adult webs. We then introduced a male onto each web and recorded his courtship behaviour, whether he successfully copulated, and whether he engaged in self-sacrifice behaviour (somersaulting and presenting his abdomen to the female).

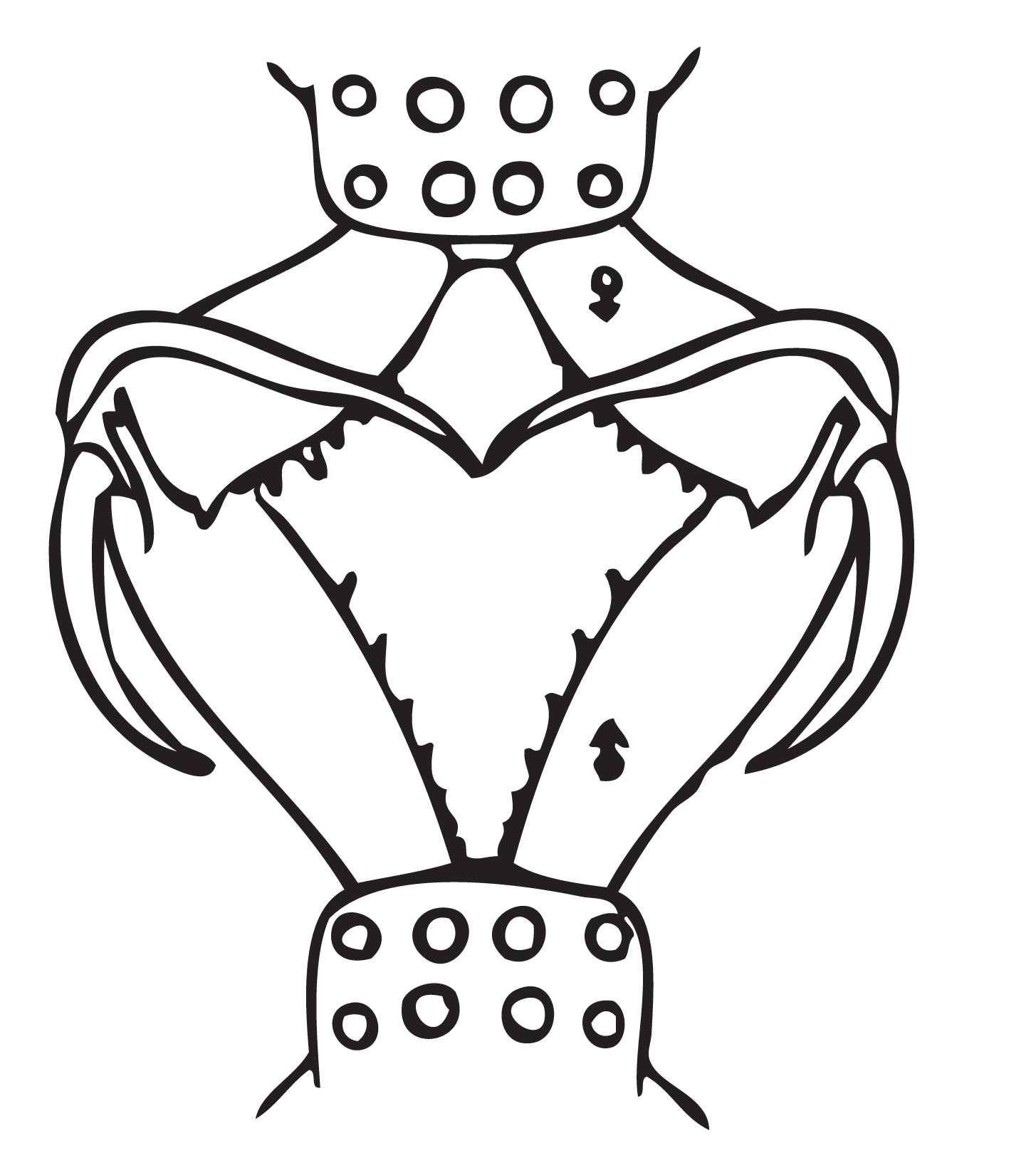

This experiment revealed that the kind of web was the main driver of an important male courtship behaviour, silk laying (part of web reduction) and of the total time the male spent courting on the web at a distance from the female. The majority of males engaged in silk laying on adult webs, and almost no males engaged in this behaviour on subadult webs, regardless of whether the female on the web was an adult or a subadult. Males also approached females much more rapidly when they were courting on subadult webs, no matter the actual status of the female on the web. These results are consistent with the idea that males invest more time into courting adult females, and that energetically costly courtship behaviours like silk laying are triggered by the sex pheromone on silk produced by adult females.

The stage of the female herself, however, determined whether males successfully mounted and copulated with females, and how long it took them to progress from one stage of mating to the next. Males were much more likely to mount adult females than subadults, and were able to mount them more quickly. Similarly, males were more likely to copulate with adults than subadults, but the time they spent engaged in courtship on the female’s body prior to copulation was much longer for adult females. This is related to the result that males much more rarely engaged in mate-binding behaviour (wrapping the female’s body with silk) when courting subadult females compared to adult females. Intriguingly, we also found that males who bound females were more likely to successfully mount, particularly when the female was a subadult. This supports the idea that mate binding functions to increase female receptivity, perhaps via a pheromone on the male’s silk.

The tiny brown widow male in this photo has reduced much of the larger female’s web, leaving a thick rope of silk that she is hanging from. Here he is laying silk on her front legs, part of the “bridal veil” or mate-binding behaviour. Photo: Sean McCann.

Finally, we found that males nearly always somersaulted during copulation with adult females, but almost never offered themselves to subadults. This indicates that the lack of sexual cannibalism during subadult mating is a result of males choosing not to engage in self-sacrifice, rather than adult females being more cannibalistic than subadults, which suggests that perhaps we should change our thinking about subadult females being the “safer” option for males.

Here the male is withdrawing his coiled embolus (one of his paired sperm-transfer organs) from the female’s genitalia. The drop of fluid on his abdomen indicates that the female bit him after he somersaulted during the first copulation. He can now copulate a second time, and again offer himself to the female so that she can complete her meal. Photo: Sean McCann

Taken together, our results confirm that male brown widows prefer to approach and attempt to mate with adults than subadults, despite the apparent advantages of subadult mating. The shortened time to mating and the lack of cannibalism, however, may be better thought of as males investing less into mating with subadults than as benefits of this tactic. This makes sense when we consider that adult females seem to be more receptive to male mating attempts than subadults, and that they are ready to produce an egg sac shortly after copulation, whereas subadults must first moult to maturity. Moulting spiders are extremely vulnerable to predators, and all the advantages of mating with a subadult disappear if she dies before producing any offspring. We conclude that mating with adults, despite resulting in a male’s death, may actually be the safer option in terms of the return (offspring) on his investment into a given female.

References & related reading: