Recluse spiders, also known as violin spiders or brown spiders (genus Loxosceles), are widely feared and generally misunderstood. If you think you’ve found one and would like more information, you’ve come to the right place!

On this page you’ll find critical information about recluse spider identification, their range in North America, bites, what to do if you you find them in your home, and links to other useful resources. First, here’s what Recluse or Not? is all about:

Recluse or Not? is a community science project led by three entomologists that aims to enhance public understanding of recluse spiders while refining our knowledge of brown recluse distribution and spider genera often mistaken for recluses.

![]()

Recluse spiders, especially the brown recluse (Loxosceles reclusa), are one of the world’s most maligned groups of spiders. Everybody thinks they know someone who’s been bitten by one, but bites are actually rare. Misdiagnoses of skin ailments as spider bites are strikingly common.

With Recluse or Not?, Catherine Scott (University of Toronto), Matt Bertone (NC State University), and Eleanor Spicer Rice (Dr. Eleanor’s Book of Common Spiders) hope to provide a platform to clear up this large-scale mistaken identity and to educate the public about these spiders. The researchers also hope to find out where these spiders are actually living. While recluses aren’t as widespread as people think, they can be found outside their native range, and that information is worth noting.

How it works: Anyone can tweet spider photos to the Twitter handle @RecluseorNot. When the Recluse or Not? team receives a photo, they’ll determine whether or not it’s a recluse spider. If it is, the team will record the spider’s location and habitat data. If it’s not, the team will record the misidentified spider’s genus.

Then the team will respond—a quick-and-easy way for the public to get an expert opinion, without harming spiders.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Range

With around 100 species, the genus Loxosceles is found through much of the world. Most species are found in North and South America (~80 spp.) and Africa, with a few species scattered in other areas (e.g. Europe has one species and China has at least two species).

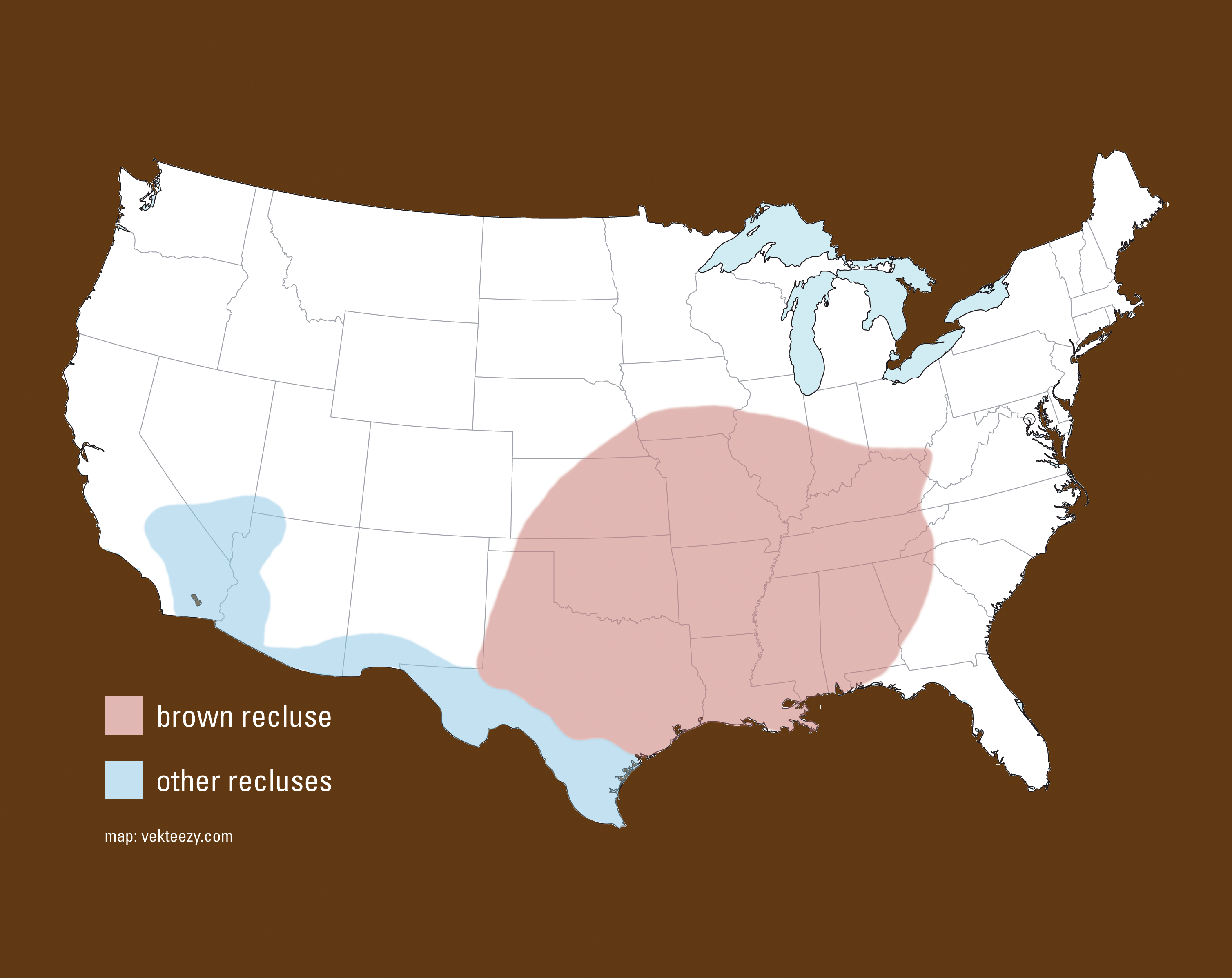

Here’s where we know recluse spiders are commonly found in North America, North of Mexico:

Inside these ranges are where you can expect to find recluses in homes or outdoors (the latter is especially true for the southwestern desert species). However, there are a few things about the range map to note:

- This map is based on the best evidence we have for areas where recluses can be commonly collected. Evidence includes scientific papers, specimens from natural history collections, and data from biologists and the pest control industry familiar with these spiders and their identification (that is, experts).

- Recluse spiders, especially the brown recluses (L. reclusa), can be transported by humans from this range to new locations. There they can survive indoors where a large population may establish and persist. This does not mean that recluses in general are spreading.For example, in North Carolina (where the spider is not native) there are known and verified populations, restricted to human structures, dating back over 40 years. Yet the spiders are very difficult to find in the state otherwise. This suggests they do not leave the homes/buildings where they establish to spread like other organisms.

- Even in the native range, brown recluses are more often encountered in homes than in the wild. We are still unsure why they are so commonly associated with homes, but we hope to learn more about this through further research.

_____________________________________________________________________________

How many species are there in the U.S.?

Several species of recluse spiders can be found in the U.S.. The brown recluse is the most widespread of the species, being found commonly in the central part of the country. In the Southwest, there are at least ten more native species, each with a small range: Loxosceles apachea, L. arizonica, L. blanda, L. deserta, L. devia, L. kaiba, L. martha, L. palma, L. russelli, and L. sabina. Their ranges can be seen here. There are also two non-native species that have turned up in the U.S. – the Mediterranean recluse (L. rufescens) and the Chilean recluse (L. laeta).

_____________________________________________________________________________

Recluse Identification

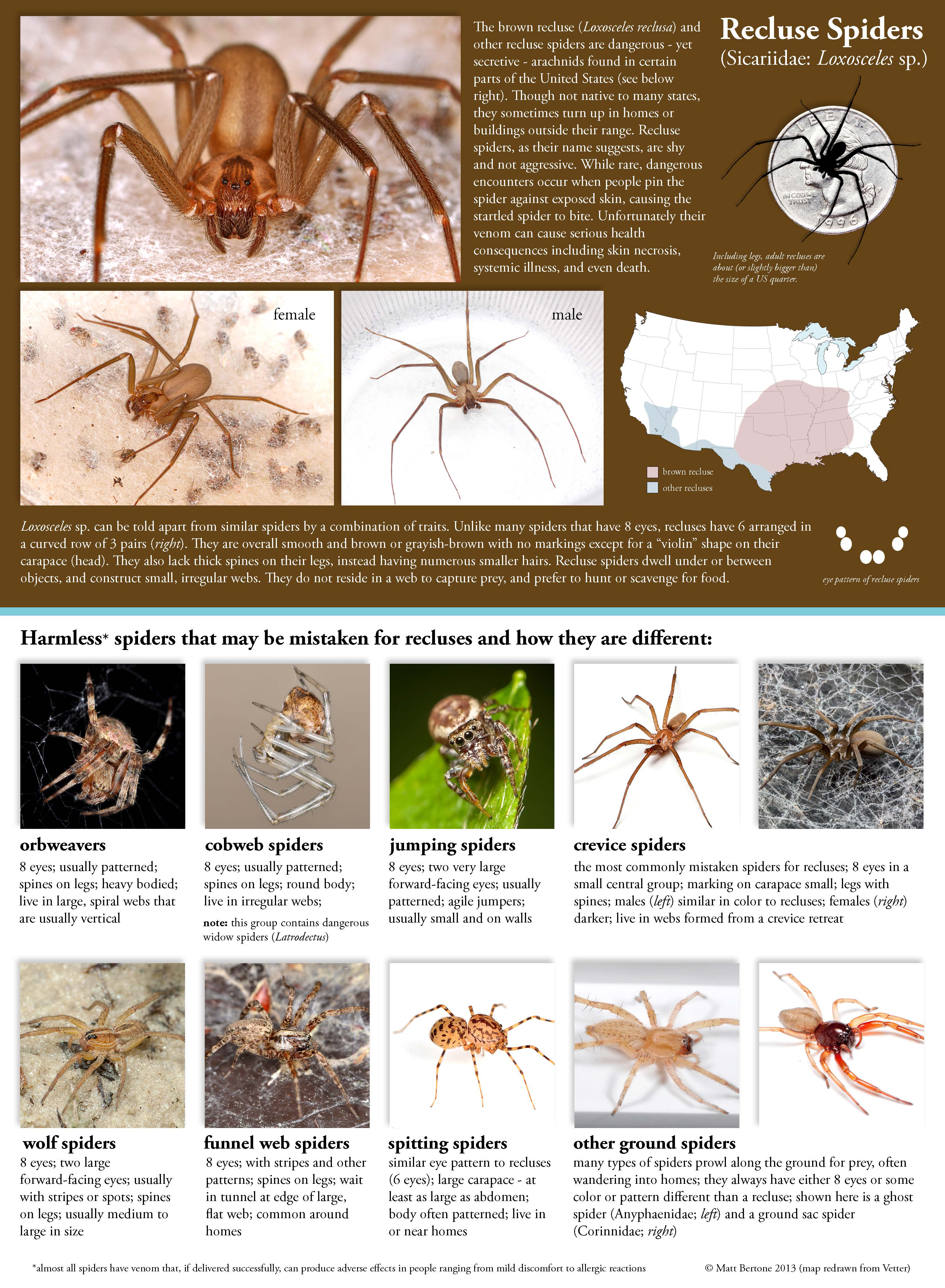

There are many great resources (and some bad ones) for identifying recluse spiders. For a quick guide to identifying them, see the infographic below. For a more in-depth treatment of their identification, please visit this page.

Still not sure? Send us your spiders (or photos of your spiders) for science!

_____________________________________________________________________________

How to safely collect and photograph a live spider

Spider catching techniques

The classic “cup and card” technique (illustrated below) is great for capturing spiders inside of homes.

Art by Jaime Van Wart for Buzz Hoot Roar.

Once you’ve got the spider in the drinking glass (or similar container) you can transfer it to a container with steep smooth sides to photograph it (see below). If a spider is needed for identification by pest control professionals or physicians, it can be transferred to a container with a lid and put in the freezer.

Spider photography techniques

Recluses are fast and generally run away from people. If they can be found sitting still, a photograph can be taken with ease and safety.

However, it is sometimes wise to capture the spider in a container (as shown above) with steep sides and photograph the spider from above. Containers with light or white insides can help with lighting when taking pictures. Make sure to take several, in-focus photos of the front of the face (eyes are diagnostic) and top of the spider; those from behind are difficult to ID.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Recluse Bites and Misdiagnosis

Recluse bites are rare but can be serious. Most (~90%) heal just fine without medical intervention and minimal scarring. It’s only the rare, very serious cases you will hear about in the media and see online. There are two forms of medically important recluse envenomations:

- Those that develop into a large, necrotic ulcer. Venom of recluses is known to sometimes cause crater-like areas of dead skin and underlying tissue that may take several months to heal. Although not life-threatening, the ulcer can be a serious condition and requires medical attention.

- Those that develop into systemic loxoscelism. In very few cases, the venom of recluses can enter the bloodstream and cause a cascade of issues, the most important of which is the mass destruction of blood cells. This can have life-threatening results, especially in the elderly, children and those with weakened health. In these cases immediate medical attention should be sought, especially if a spider is directly involved.

Only a handful of recluse bites have ever been recorded to cause death in people.

Unfortunately, without a spider or direct evidence, people often assume any red “bite” or necrotic skin issue is from a spider or recluse in particular. Spiders are not interested in randomly biting people. True cases of spider bites come when the spider is pressed up against the skin and the spider is under the threat of being crushed. Many of these “bites” are other skin conditions, from harmless ones like ingrown hairs, pimples, and small scratches, to very serious bacterial skin infections (for example, MRSA). In fact, even if a spider does bite, the actual venom may not cause issues, but the bite area may become seriously infected (as can happen when any organism or object pierces the skin). Below is a list of conditions that can be confused for recluse bites (source):

Bacterial Infection: Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Lyme borreliosis, Cutaneous anthrax, Syphilis, Gonococcemia, Rickettsial disease, Tularemia, Ecthyma gangrenosum, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Deep fungal Infection: Sporotrichosis, Aspergillosis, Cryptococcosis

Parasitic infection: Leishmaniasis

Viral Infections: Herpes simplex, Herpes zoster

Atypical mycobacterial Infection: Mycobacterium ulcerans, Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Environmental pathogens: Chromobacterium violaceum

Vascular occlusive or venous disease: Antiphospholipid-antibody syndrome, Livedoid vasculopathy, Small-vessel occlusive arterial disease, Venous statis ulcer

Necrotizing vasculitis: Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, Polyarteritis nodosa, Takayasu’s arteritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis,

Cancers: Leukemia cutis, Lymphoma (mycosis fungoides), Primary skin neoplasms: Basal-cell carcinoma, Malignant melanoma, Squamous-cell carcinoma

Topical: Chemical burn, Thermal burn, Poison ivy, Poison oak

Other conditions: Calcific uremic arteriopathy, Cryoglobulinemia, Diabetic ulcer, Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis, Lymphomatoid papulosis, Other arthropod bites, Pemphigus vegetans, Pyoderma gangrenosum, Pressure ulcers (bed sores), Radiotherapy, Self-induced injury, Septic embolism

Here is a little check list for helping to determine if you were bitten by a recluse:

- Was there a sharp pain? In the rare cases where recluses do bite, the fangs are small and there is typically no initial pain from the bite; symptoms show up a little later

- Did it happen outside? Then it is likely not from a recluse as they are non-existent or uncommonly found outdoors through much of the U.S. and Canada (but note that some of the Southwestern species are common in nature, usually under rocks and debris)

- Were recluses found in the house where the “bite” occurred? If not then it is likely something else; where they exist, recluses can typically be found in large numbers

- Is the ulcer filled with pus or weeping? This is most likely evidence of a bacterial infection, not a recluse bite; a physician should be seen and material from the wound should be cultured to determine if bacteria are present

All in all, spider bites (and recluse bites) are rare, especially if a spider was not directly involved. True bites typically involve a hand or foot stuck in the wrong place, feeling the spider bite, and then seeing a dead or suspicious spider nearby. But did you wake up and find a curious little red bump? Almost certainly not from a spider…

_____________________________________________________________________________

So you’ve got recluses – what now?

The first thing to do is not panic. As stated before, bites are uncommon even where recluses exist in high numbers. However, to reduce exposure to the spiders, proper caution should be taken reaching into places or under things in infested areas. Shoes, clothing, and linens should be checked before use, so no spiders are accidentally pressed against the skin. Beds can be pulled away from the wall a short distance and the legs protected using traps or sticky barriers.

Unfortunately fully eliminating recluses is difficult due to their shy nature and ability to build up large populations indoors. Sticky cards/traps can be put around the perimeter of rooms for monitoring or in areas of high infestation. Note that they will likely not lead to complete control, but will take some spiders out of the population. They will also help identify levels of infestation after chemical control (see below). Note that sticky traps are not specific in what they catch and can catch non-target organisms.

A local pest control service should be contacted to deal with moderate to severe infestations. These services bring training and experience to help you solve the problem. They should be able to recommend options for control that are as effective as possible, all while following proper laws and guidelines. Control will likely be a long process. If a homeowner wishes to treat the house themselves, choose EPA (USA) or PMRA (Canada) registered pesticides suitable for indoor use and follow the label carefully. Homeowners should not apply homemade sprays or use store-bought pesticides in a manner other than what the label states — improper chemical usage can be much more dangerous than the spiders themselves.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Who are we?

Catherine Scott is an arachnologist and behavioural ecologist who studies sexual communication in spiders. She is currently a PhD student at the University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada, where her research is focused on black widow spiders. A former arachnophobe, she now spends much of her free time outside searching for spiders and learning new things about their secret lives. Catherine is passionate about trying to shift perceptions about these fascinating and often misunderstood creatures by engaging in science communication online and in person.

Matt Bertone is an extension associate in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology at North Carolina State University. He is the entomologist for the Plant Disease and Insect Clinic where he identifies insects and other arthropods for the public, industry, government, and researchers. He has long been fascinated with the world of “creepy crawlies”, especially their biology, habits, and evolution (particularly taxonomy and systematics). Matt has a special place in his heart for spiders and other venomous animals. He is also an avid macrophotographer.

Matt Bertone is an extension associate in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology at North Carolina State University. He is the entomologist for the Plant Disease and Insect Clinic where he identifies insects and other arthropods for the public, industry, government, and researchers. He has long been fascinated with the world of “creepy crawlies”, especially their biology, habits, and evolution (particularly taxonomy and systematics). Matt has a special place in his heart for spiders and other venomous animals. He is also an avid macrophotographer.

Eleanor Spicer Rice is an entomologist and science writer living in Raleigh, North Carolina. After completing her Ph.D. in entomology at North Carolina State University, Eleanor began writing about the exciting and wonderful entomological things she learned, including on her blog, Buzz Hoot Roar, and in her Dr. Eleanor’s Book of Common Ants series (University of Chicago Press), and Dr. Eleanor’s Book of Common Spiders, with Chris Buddle (University of Chicago Press, January 2018).

_____________________________________________________________________________

Other resources & further reading

Genus Loxosceles on BugGuide

Rick Vetter is a recently-retired, world expert on brown recluses and has published a number of papers on the subject. Here are some of his helpful resources:

Rick Vetter’s website

Vetter’s book: The Brown Recluse Spider

Vetter, R. (1999). Identifying and misidentifying the brown recluse spider. Dermatology Online Journal, 5(2).

Bennett, R. G., & Vetter, R. S. (2004). An approach to spider bites. Erroneous attribution of dermonecrotic lesions to brown recluse or hobo spider bites in Canada. Canadian Family Physician, 50(8):1098-1101. pdf

Vetter, R. S. (2000). Medical Myth: idiopathic wounds are often due to brown recluse or other spider bites throughout the United States. Western Journal of Medicine, 173(5):357.

Vetter, R. S., Cushing, P. E., Crawford, R. L., & Royce, L. A. (2003). Diagnoses of brown recluse spider bites (loxoscelism) greatly outnumber actual verifications of the spider in four western American states. Toxicon, 42(4):413-418. pdf

Vetter, R. S., & Bush, S. P. (2002). Reports of presumptive brown recluse spider bites reinforce improbable diagnosis in regions of North America where the spider is not endemic. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 35(4), 442-445.

Vetter, R. S., Edwards, G. B., & James, L. F. (2004). Reports of envenomation by brown recluse spiders (Araneae: Sicariidae) outnumber verifications of Loxosceles spiders in Florida. Journal of Medical Entomology, 41(4), 593-597.

Vetter, R. S., & Barger, D. K. (2002). An infestation of 2,055 brown recluse spiders (Araneae: Sicariidae) and no envenomations in a Kansas home: implications for bite diagnoses in nonendemic areas. Journal of Medical Entomology, 39(6), 948-951.

Swanson, D. L., & Vetter, R. S. (2005). Bites of brown recluse spiders and suspected necrotic arachnidism. New England Journal of Medicine, 352(7), 700-707. pdf