Bolas spiders (members of the genus Mastophora, in North America) are famous for their unusual prey capture technique: rather than a web, they produce a single silk line with a super-sticky ball of glue at the end, which they fling at their prey.

Female Mastophora cornigera hunting with her ‘bolas’. (Photo: Matt Coors)

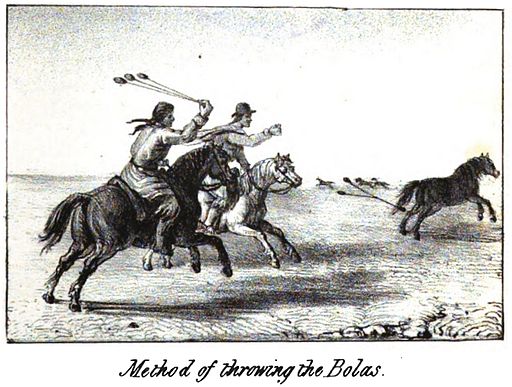

The common name ‘bolas spider’ is not particularly accurate, though. A real bolas – two or more weights connected by cord – is swung and thrown at an animal (like a horse, in the image below) in its entirety, and works by getting tangled around the legs of the target.

The spider’s ‘bolas’ differs in that it never leaves its owner’s grip, and works by getting stuck to the target, which is invariably a moth.

Eberhard (1980) observed that a more appropriate name would be “sticky yo-yo spiders”. The sticky yo-yo prey capture technique is impressive enough (inspired by their speed and accuracy with the bolas, Eberhard named one species

dizzydeani for Jerome “Dizzy” Dean, one of the greatest baseball pitchers of all time), but to fully appreciate the wonders of bolas spider biology, we must delve into the secret lives of these aromatic and cryptic spiders. They are masters of deception, both olfactory and visual.

Seductive scents

Hunting with a sticky yo-yo is all very fierce and exciting, but what are the chances that a moth is ever going to fly close enough for the spider to swing at? Not very high. Unless, like the bolas spider, you have a trick or two up your sleeve… er, leg… coverings. Adult female bolas spiders have the incredible ability to produce a chemical cocktail that make them smell just like female moths advertising for mates (actually, no one knows yet which part of the spider’s body is responsible for this wonderful trick). Innocent male moths following what they perceive to be a pheromone trail (whose chemical message indicates that it leads to a sexually receptive female moth) are thus duped into coming in close enough for the spider to strike. This is called “aggressive chemical mimicry”, and it is awesome.

Moth sex pheromones are typically blends of two or more chemical compounds in very specific ratios. The particular chemicals and ratios allow male moths to discriminate between females of their own and other species. If a bolas spider produced just one moth pheromone, they probably wouldn’t do very well, because their diet would be restricted to only a single moth species. It turns out that each species of bolas spider attracts several kinds of male moths, and the best studied of these is Mastophora hutchinsoni.

Mastophora hutchinsoni attracts four kinds of moths, but more than 90% of their prey consists of two species in the family Noctuidae: the smoky tetanolita (Tetanolita mynesalis) and the bristly cutworm (Lacinopolia renigera). These two moth species produce entirely different sex pheromones, and they are active at different times of night. The problem for the bolas spider is that the bristly cutworm pheromone interferes with the attractiveness of the smoky tetanolita’s pheromone.

Here’s where the bolas spiders start to get really fancy. Let’s join an M. hutchinsoni female for a night of hunting, and learn some of her secrets.

M. cornigera female preparing for a night of moth hunting. (Photo: Matt Coors)

She begins by building her horizontal “trapeze” line, from which she then hangs motionless, with front legs extended in hunting position (but with no bolas, yet). She is already emitting the sex pheromones (well, analogs that are close enough!) of both prey species, but so far, only the early-flying bristly cutworm is active. They aren’t put off by the smell of smoky tetanolita females mixed in with the pheromone of a female of their own species, and soon one is winging its way toward the seductive scent coming from the female spider. It passes close by, but out of reach. This moth is lucky, for now. But no matter; his fate is not our immediate concern. The spider’s outstretched legs are covered with tiny vibration-sensitive hairs (called trichobothria) that allow her to detect the sound of the moth’s wing beats nearby. Now that she knows there is prey about, she springs into action and spends the next minute or two building her sticky bolas.

Female M. cornigera hunting with her bolas. (Photo: Matt Coors)

Once her weapon is complete, she returns to her prey-capture position, with the bolas hanging from one of her outstretched front legs. For her next trick, she will again rely on her ability to detect the wingbeats of flying moths with her leg hairs. She waits patiently, silent and still.

Soon, another hapless male moth picks up the scent and starts winging towards the bolas spider. When her sensory hairs tell her the time is just right, she takes a swing at the approaching moth and connects. Although the moth struggles, shedding scales in its effort to escape, the wet stickiness of the bolas holds it fast. The spider reels the moth in and delivers a fatal venomous bite. She waits a few moments, then wraps her prize in swathes of silk and hangs it carefully from her trapeze line to eat later. The night is young, and the moths will continue flying for some hours yet. The bristly cutworms will remain active until 22:30. Our spider builds a fresh bolas, and settles in to wait. Gradually, the smell of bristly cutworm sex pheromone coming from the spider fades. The smell never disappears entirely, but is soon faint in comparison to the scent of a female smoky tetanolita. The smoky tetanolita males will come out after 23:00, and our spider will be ready for more deadly deception.

So far, we’ve discovered some of the adult female bolas spider’s secrets to success, but what about juveniles and males? They don’t use a bolas, but they are no less stealthy and deceitful than their counterparts. Young bolas spiders are also employ aggressive chemical mimicry to attract prey, but they specialize on male moth flies in the family Psychodidae. Each bolas spider species is especially attractive to a particular species of moth flies. It appears to be a pleasing coincidence that small bolas spiders prey on moth flies until they graduate to real moths. Whether or not the sex pheromones of the psychodids captured by each spider are similar to those of moths they specialize on is currently a mystery.

Optical illusions

Mastophora females are not only masters of chemical deception, but they are also visually cryptic, and hide in plain sight from their own potential predators. They do this by mimicking bird poop.

Excellent bird-poop mimicry by Mastophora cornigera. (Photo: Matt Coors)

The female spiders spins herself a silken mat on the surface of a leaf, and clings to it with her legs drawn in tightly around her cephalothorax.

Another bird poop mimic, female M. phrysonoma, with visitors! (Photo: Matt Coors)

But wait, what are those tiny red things? At first glance, they could easily be mistaken for mites, but no! These are tiny males, presumably interested in mating with the comparatively massive female. Bolas spider males are usually less than 2 mm long, while females are typically 10 – 15 mm long, and sometimes as large as 2 cm!

Another shot of the incredible bird poop mimicry and extreme sexual dimorphism of M. phrysonoma. (Photo: Matt Coors)

Because the females are so cryptic and males are so tiny, almost nothing is known about the sexual behaviour of bolas spiders. As a researcher studying sexual communication and mating behaviour in spiders, I sure would love to know how the males in the photos above found the female and what happened next! Most likely, the female bolas spiders produce attractive sex pheromones just like the moths whose chemical communication they exploit. As far as I am aware, however, no one has investigated the sex pheromones of bolas spiders. One hypothesis that might explain the evolution of their mimicry of moth pheromones is that their own chemical signals have compounds in common with those of their prey. In fact, this is a hypothesis that Andy Warren is investigating for a different group of spiders that also mimic moth pheromones – orb weavers in the genus Argiope.

If you’re not familiar with spider systematics, it might seem odd that two groups of spiders that look so different and have such different prey-capture techniques share the amazing ability to lure male moths to their doom. In fact, bolas spiders are orb-weavers (at least, they are members of the orb-weaver family Araneidae), they just don’t build webs like most of their relatives. Like orb-weavers, bolas spiders regularly eat their silken traps and recycle the silk proteins to use another day.

See the family resemblance?

To see a female bolas spider in action, check out this video clip from David Attenborough’s “Life in the Undergrowth” series. (The bolas spider segment starts at 3:00, but the first few minutes about the redback spider are also worth a watch!)

Special thanks to Matt Coors for kindly letting me feature his fantastic photographs in this post!

References:

Eberhard, W. G. (1980). The natural history and behavior of the bolas spider Mastophora dizzydeani sp. n. (Araneidae). Psyche: A Journal of Entomology, 87(3-4), 143-169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/1980/81062

Haynes, K. F., Yeargan, K. V., & Gemeno, C. (2001). Detection of prey by a spider that aggressively mimics pheromone blends. Journal of insect behavior,14(4), 535-544. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1011128223782

Haynes, K. F., Gemeno, C., Yeargan, K. V., Millar, J. G., & Johnson, K. M. (2002). Aggressive chemical mimicry of moth pheromones by a bolas spider: how does this specialist predator attract more than one species of prey? Chemoecology, 12(2), 99-105. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00049-002-8332-2?LI=true

Yeargan, K. V. (1988). Ecology of a bolas spider, Mastophora hutchinsoni: phenology, hunting tactics, and evidence for aggressive chemical mimicry. Oecologia, 74(4), 524-530. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4218505

Yeargan, K. V. (1994). Biology of bolas spiders. Annual review of entomology, 39 (1), 81-99. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.en.39.010194.000501

Yeargan, K. V., & Quate, L. W. (1996). Juvenile bolas spiders attract psychodid flies. Oecologia, 106(2), 266-271. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00328607

Yeargan, K. V., & Quate, L. W. (1997). Adult male bolas spiders retain juvenile hunting tactics. Oecologia, 112(4), 572-576. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s004420050347