This post features photographs by Sean McCann. For more beautiful photography and natural history of arthropods and other wildlife, check out his blog, Ibycter.com.

As a sequel to our recent encounter with some long jawed orb-weavers in the genus Tetragnatha (the tiny and cryptic Tetragnatha caudata), this week on an evening walk at Iona Beach, Sean and I observed some neat predation and mating behaviour in another species, most likely Tetragnatha laboriosa.

We made our first observation just as the sun was beginning to set, the beginning of the most active hunting hours for Tetragnatha laboriosa. This female had just captured her first meal of the evening, a bug in the family Miridae.

After biting it, she began wrapping it with silk, which she pulled out of her spinnerets with her last pair of legs (you can see her caught in the act below).

After wrapping the bug lightly with silk, she carried it back to the hub of her orb web and settled down to dine.

Unfortunately for the spider, dinner was interrupted by Sean’s efforts to get a good photograph. The disturbance prompted her to drop her meal and retreat to the vegetation at the edge of her web. Isn’t she just gorgeous?!

After a minute or so, she went back for her abandoned prey.

She then carried it off the web to resume her meal in peace. You can see from this image how the lovely coloration of these spiders allows them to blend in with plant stems when they adopt their cryptic stick-like posture.

Later, when the sun had all but set and we were just about to head home, Sean spotted a pair of spiders (probably the same species, T. laboriosa) mating in a female’s web.

Mating involves a fair bit of contortion for long jawed orb-weavers. Below you can see the male’s extremely long pedipalp (one of a pair of appendages modified for transferring sperm) engaged with the female’s epigyne (genital opening). The male’s short third pair of legs is used to position his partner’s abdomen. Throughout copulation he maintains a firm grip on the female’s jaws with his own.

Here is a closer look at the mating position, where if you look closely you can see one of the female’s fangs interlocking with the special tooth on the male’s corresponding chelicera.

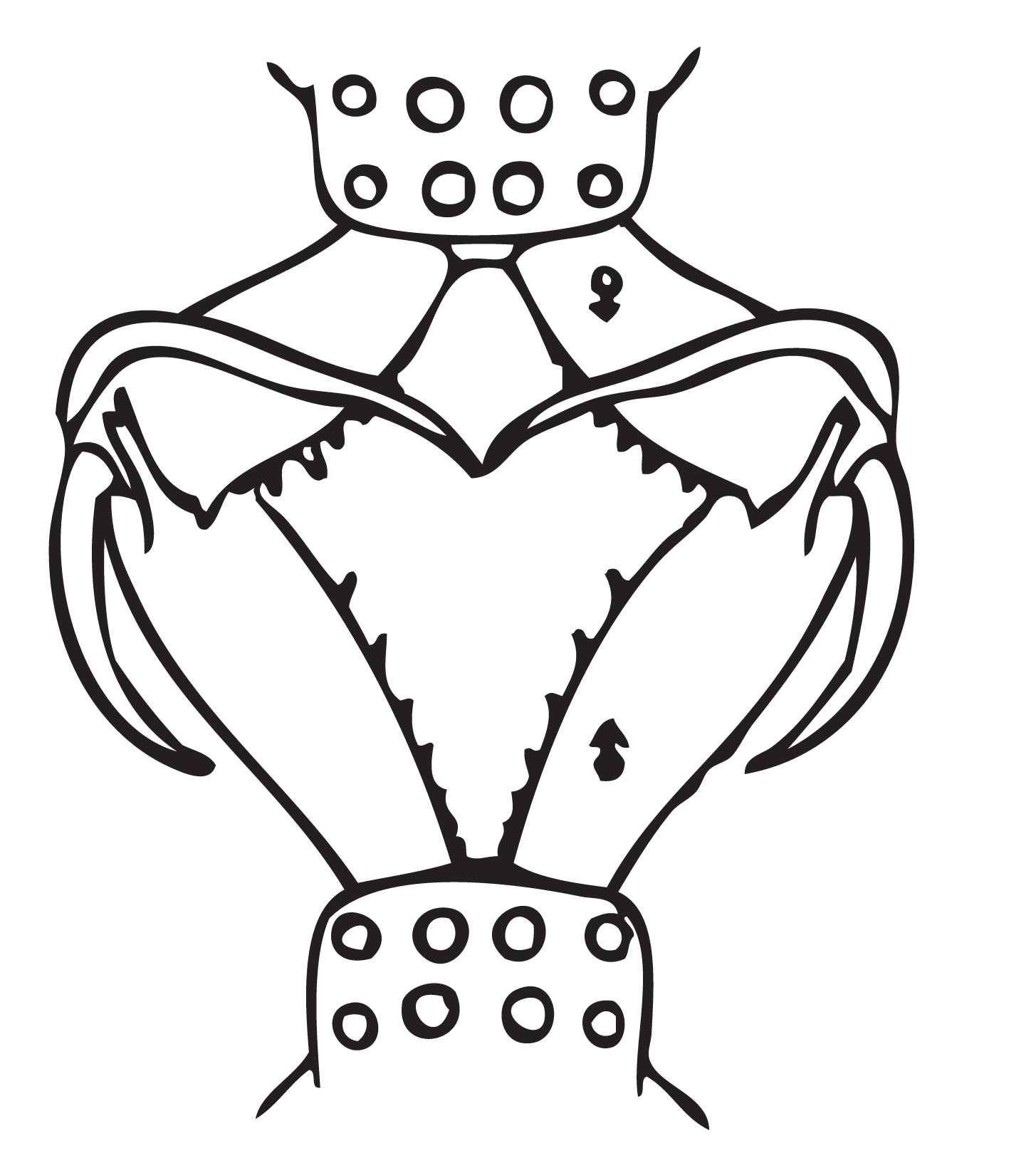

Here is a drawing by B. J. Kaston of what the cheliceral embrace looks like close-up. The male, with larger jaws, is below, and the female above.

Fig. 876 from Kaston 1948. Interlocking jaws of Tetragnatha pallescens (which looks very similar to T. laboriosa) during mating.

The female’s fangs get locked in underneath the special large tooth that protrudes from each of the male’s chelicerae.

As if we hadn’t had enough excitement already with the chance to closely witness such an intimate encounter, moments later we spotted two additional males waiting in the periphery of the female’s web. We were in for quite a show!

Here is one of the males that was waiting in the wings, posing elegantly and displaying his long jaws and even longer pedipalps. We’ll call him bachelor #2.

Not long after we spotted them, one of the lurking males made his move, lunging at the mating pair with his jaws held wide.

A bit of a tussle ensued, after which the mating spiders disengaged. The attacking male pursued the mated male off the web and all the way to the substrate below. The female, apparently rather perturbed by this rude interruption, also left the web. One of the two rival males, apparently dominant, soon ascended back toward the web via his dragline.

Just as the winner of the first brief battle returned to the web, the third male entered the ring, and a second chase ensued. This cycle repeated a couple of times, until at last only one male returned victorious to the periphery of the web.

Bachelor # 2 (or was it #3?) settled down to wait at the edge of the web, while the female made her way back to the hub.

It turns out that female T. laboriosa only mate once as a rule, and if copulation is interrupted as we observed, it’s a toss-up whether or not she will be willing to pick up where she left off (LeSar & Unzicker 1978). We couldn’t stay to see if our champion was able to successfully mate, but we wished him the best of luck!