This post is a summary of a recently-published paper (and related open-access dataset) that was a very fun collaboration led by Stefano Mammola, Angela Chuang, Jagoba Malumbres-Olarte and 61 other arachnologist colleagues* from around the world.

This study was largely motivated by our collective frustration at the often inaccurate and sensational way that spiders are portrayed in the media. But just how bad is the quality of reporting on spiders, and why is it so pervasive?

To answer these questions and understand how misinformation about spiders flows at the global scale, we amassed a team of experts from all over the world to analyze 10 years of online news stories about human-spider encounters. We first searched Google News (using variations on the search term “spider AND bite”) to find more than 5000 news articles from 81 countries published in 40 languages. We then read each paper to collect data including the date and location of each reported event, whether the story described a human-spider encounter (but not a biting event) or a “bite” or “deadly bite” (spoiler: articles rarely included evidence of an actual spider bite), and checked each news item for errors (e.g., misidentified spiders in photos, incorrect information about spider biology or venom) and sensationalism (somewhat subjective**, but often based on the inclusion of words like “horror”, “terrifying”, and “deadly” ). We also recorded whether the article quoted an expert, and whether they were a medical professional, a spider expert (usually an arachnologist or entomologist), or “other” (e.g., a pest management professional). All of this data, detailed methods, and a summary of what we found broken down by continent is freely available online here.

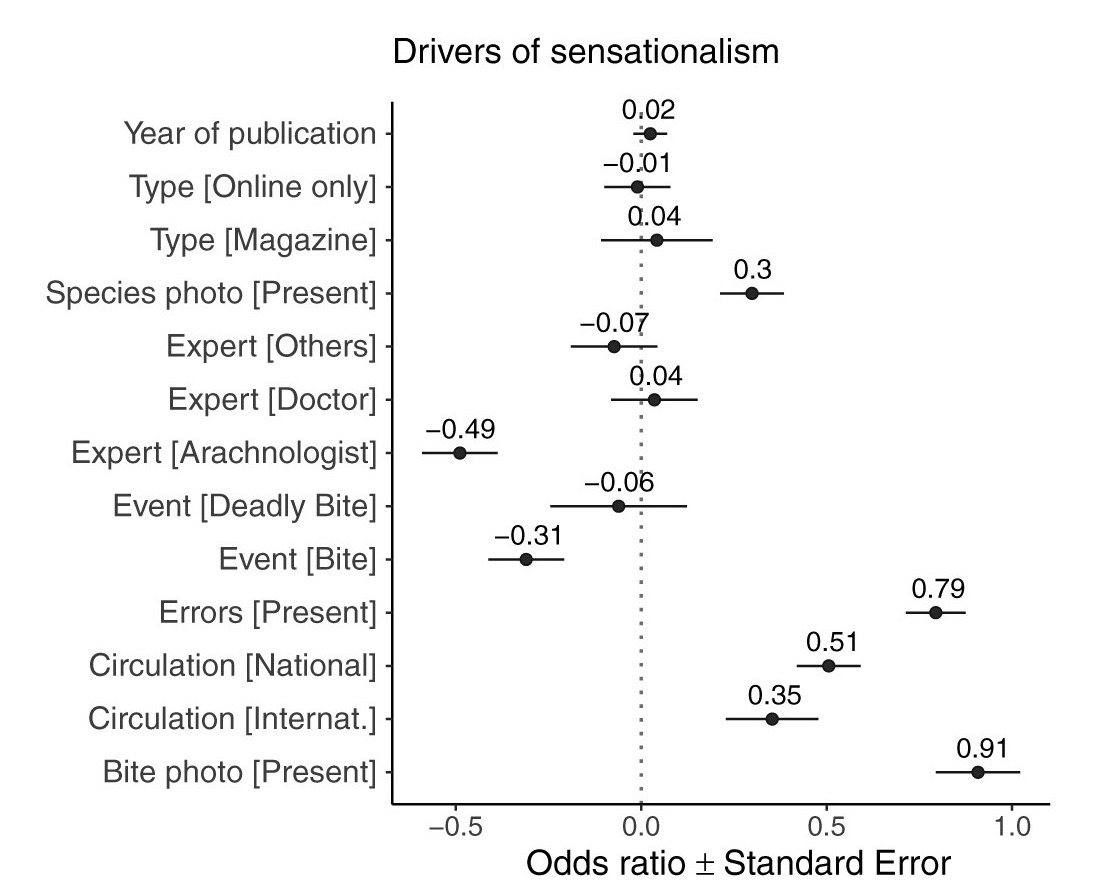

Overall, the quality of the reporting was poor: 47% of all articles contained one or more errors and 43% were sensationalist. Stories with photos of spiders or alleged bites were more likely to be sensationalized, as were stories that contained errors. Whereas quotes from medical or other experts were unrelated to sensationalism, stories that contained quotes from spider experts were much LESS likely to be sensationalized.

One of our plans for the future is to create a global database of arachnological experts to make it easier for journalists to identify and contact arachnologists in their region who are willing to be interviewed and provide factual information about spiders. We are also already working on a paper outlining guidelines for journalists covering spider news stories, which we hope will help to prevent some of the most common errors we saw and improve the overall quality of reporting.

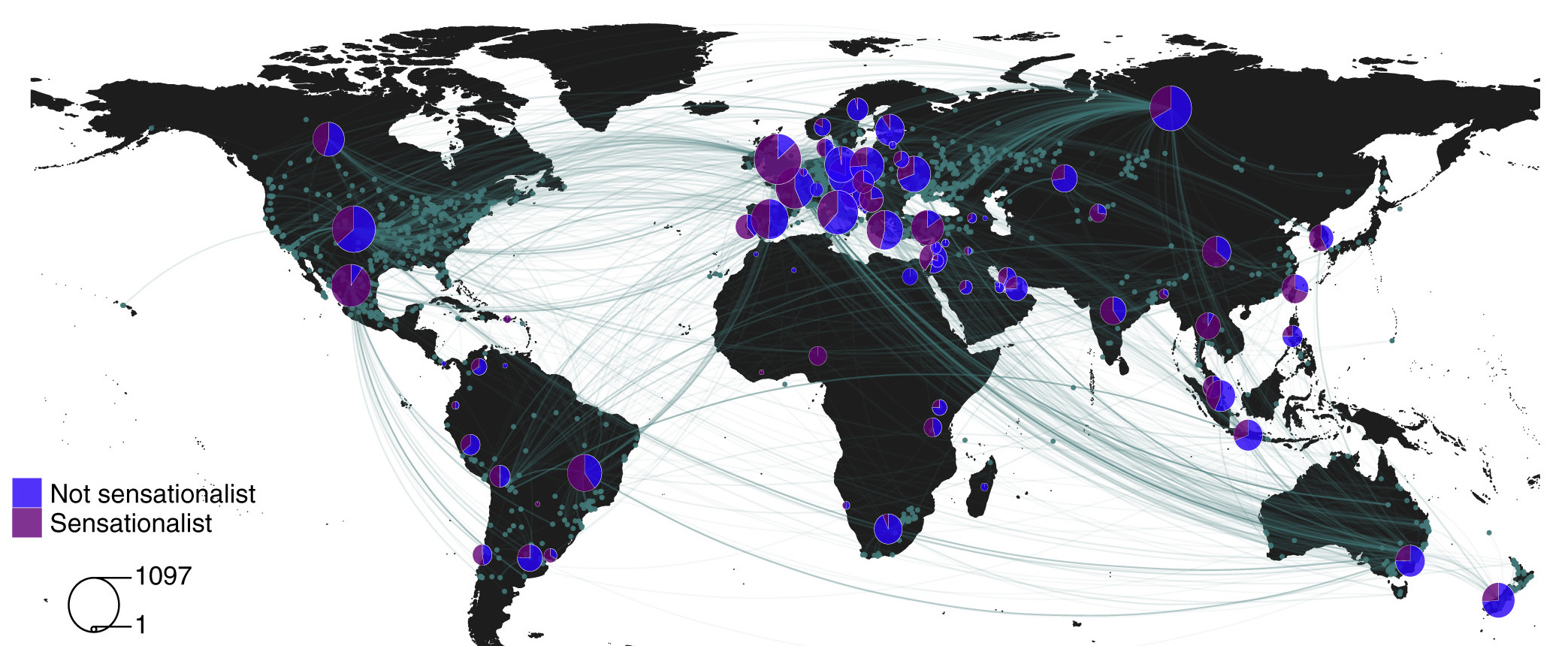

We next conducted an analysis to describe the flow of spider news stories around the world and to get at what may be driving the spread of (mis)information about spiders online. Unsurprisingly, countries with shared languages and with higher proportions of internet users were more likely to be connected in the global network. The number of medically important spider species present (i.e., those capable of harming and potentially killing humans) also increased the connectedness of individual countries within the network. Most notably, we identified sensationalism as a key factor underlying the spread of (mis)information.

This study provides insight into what drives the global flow of information about spiders in particular, but can also teach us some more general lessons. Our results make us optimistic because they suggest a way to improve reporting on spiders, and in turn, to shift the quality and spread of online information more broadly. News stories are less sensationalized when they consult appropriate experts, and reducing sensationalism can help decrease spread of misinformation. We found that even local-scale events published by regional news outlets can quickly become broadcast internationally, which means improving news quality at the local scale can have positive effects that travel through the global network.

**For the news in English, Spanish, French, and Italian we checked to see how closely scores aligned for different collaborators assessing the same article, and we were pretty consistent.