Yes, this is a blog about spiders, and no, pseudoscorpions are not spiders. But they are members of the class Arachnida, like spiders, and fascinating, like spiders! I encountered them for the first time on a recent trip to the Okanagan with Sean, so here’s a post about some of their natural history.

Two tiny pseudoscorpions Sean and I found while doing some rock flipping on a hillside near Vaseux Lake, BC. Photo: Sean McCann

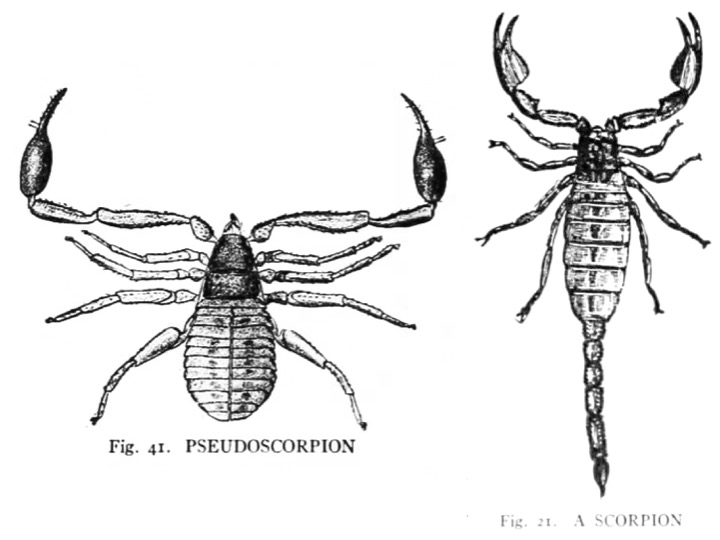

Pseudoscorpions are really weird, and really awesome, creatures. Their name means “false scorpion” (which is also a common name for this order of arachnids), because superficially they look a lot like scorpions (members of another arachnid order), minus the “tail” with its stinger on the end.

Drawings of a pseudoscorpion and a scorpion from JH Comstock’s book. The illustrations are most likely by Anna C. Stryke, but possibly by Mrs. Comstock. Note that the scale is different for each drawing.

Pseudoscorpions are tiny. The one below (photographed under a microscope) is only about 1 mm long! The largest pseudoscorpions can get as long as 10 mm. Their small size means they can live in tight spaces, like between floorboards, under tree bark, or even under the elytra (hardened forewings) of beetles – but more on this later.

Pseudoscorpion found in Vero Beach, FL. Photo: Sean McCann

Pseudoscorpion morphology is strange. Like other arachnids, pseudoscorpions have two main body segments: a cephalothorax (the front part, a combined head-and-thorax bearing all of their appendages), and an abdomen. They may have one or two pairs of simple eyes on the sides of the cephalothorax (or none at all) and their vision is generally poor. As well as four pairs of legs, they have enormous chelate (pincer-like) pedipalps that they use for capturing prey and sensing their environment.

A neobisiid pseudoscorpion nicely displaying its chelate jaws and pedipalps. Photo: Marshal Hedin, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

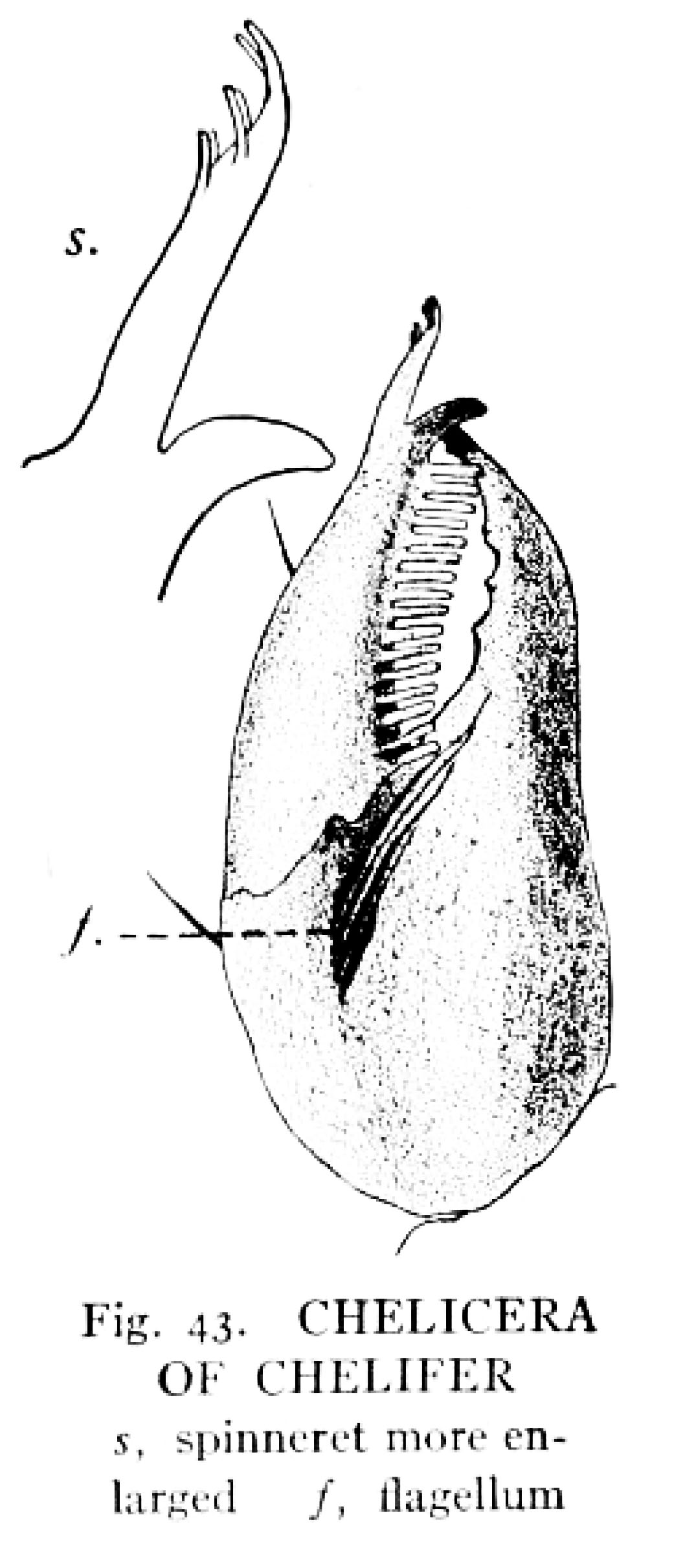

Pincer-like chelicera (singular of chelicerae) of a pseudoscorpion, bearing spinnerets on the movable finger. From Comstock’s book.

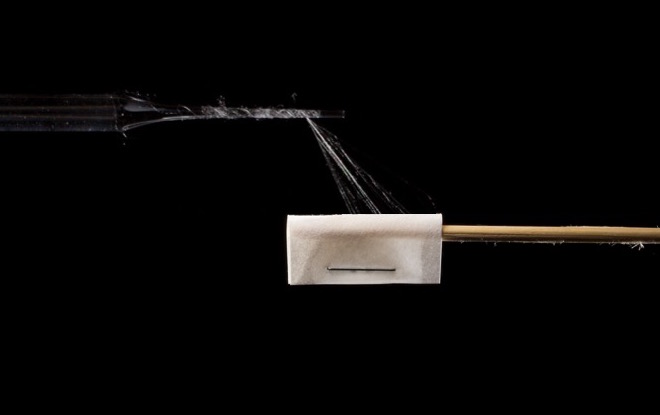

Their jaws (called chelicerae) are also like miniature pincers. Like spiders, pseudoscorpions can produce silk. Unlike spiders, who have abdominal silk glands and spinnerets, pseudoscorpions’ silk glands are in their cephalothoraxes, and their spinnerets are on the tips of their chelicerae! (The spitting spiders in the family Scytotidae are exceptional among spiders in also having silk glands in their cephalothoraxes, and “spitting” the silk out of their fangs along with venom.)

Pseudoscorpions use silk to build retreats* or cocoons for moulting, overwintering, and sometimes brooding their young.

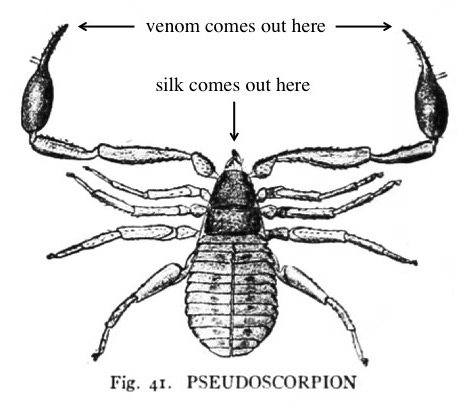

Also like spiders, many pseudoscorpions use venom to subdue their prey, which includes mites and other tiny arthropods. The venomous pseudoscorpions are in suborder Iocheirata, which means “poison hands”. Their venom glands are in their modified pedipalps, with openings in the tips of one or both of the fingers of their claws.

To me, pseudoscorpion anatomy is all topsy-turvy (at least compared to spiders): their silk comes out the wrong end and their venom comes out of clawed “hands” instead of fangs.

Pseudoscorpion – modified from the illustration in Comstock’s book.

Pseudoscorpions also have pretty strange reproduction. Males deposit a spermatophore (a package of sperm) on the ground, which a female must then pick up and insert into her reproductive opening. Males of different kinds of pseudoscorpions have various methods of ensuring that a female finds and uses their sperm. Some are carefree: the male deposits the spermatophore, walks away and (figuratively) crosses his fingers and hopes that a female will encounter it by chance. Other tactics are rather more direct and reliable: the male engages the female in an elaborate “mating dance” and eventually pulls her over his spermatophore to ensure that she picks it up. In one species, Serianus carolinensis, males only produce spermatophores when a female is nearby, then they spin special silk webs that direct her to the package.

Once a female’s eggs are fertilized, she keeps them in a brood pouch under her abdomen (or sometimes next to her in a silken brooding chamber). This brood-sac contains food for the developing pseudoscorpion embryos, which grow and moult into protonymphs (juveniles that look just like adults, but smaller) before emerging.

A female Arctic pseudoscorpion, Wyochernes asiaticus, with her brood pouch. Photo: Crystal Ernst (used with permission)

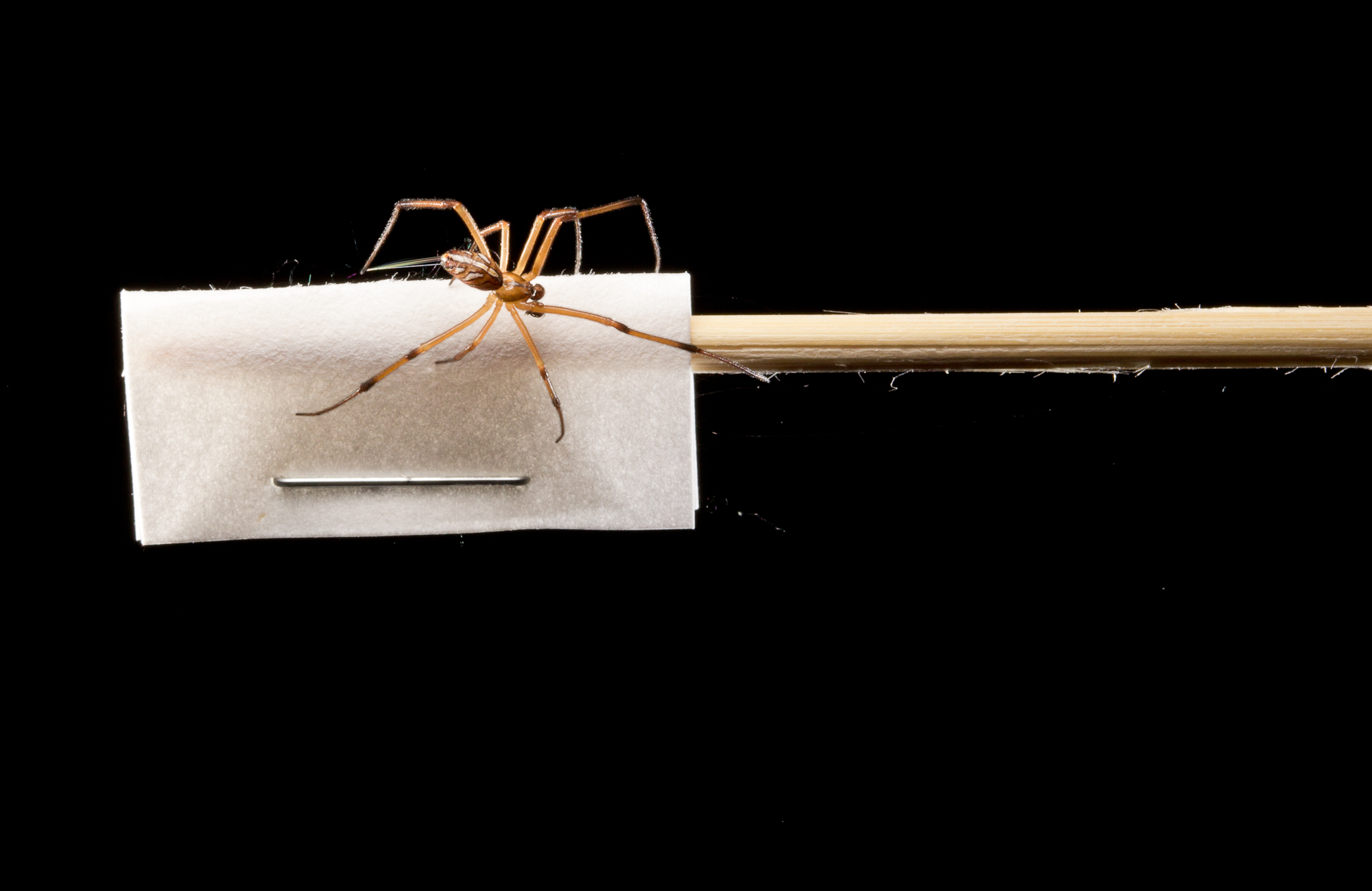

Pseudoscorpions love books! Although I would like to think the little pseudoscorpion in the photograph below enjoys reading, what they really like about books is the booklice that sometimes live in them. Because pseudoscorpions can sometimes be found living between the pages of books and feeding on booklice, one common name for them is “book scorpions”.

“Book scorpion” enjoying some literature while waiting for booklice. Photo: Sean McCann

Finally, pseudoscorpions are hitchhikers! Because they are so small and don’t fly, pseudoscorpions can’t get very far on their own. To overcome this obstacle, they hitch lifts on other organisms – usually larger arthropods like beetles and flies. This particular kind of symbiosis – in which the individual doing the carrying is apparently unharmed – is called phoresis.

A longhorn beetle, Xylotrechus sagittatus, with phoretic pseudoscorpions hitching a ride on its leg. Photo: Sean McCann

Phoresis is a fantastic word that comes from Greek: phor means “carry, bear; movement” but it can also mean “thief”. Phoretic pseudoscorpions latch onto the bodies of their transportation with their pincers to steal a free ride. Some pseudoscorpions are stowaways under the elytra of comparatively gigantic harlequin beetles, and feed on phoretic mites and find mates while they travel. Piotr Naskreki has a wonderful blog post with pictures of these tiny ecosystems on a beetle’s back.

A closer view of the cluster of tiny travelers. Photo: Sean McCann

Want to find out more about pseudoscorpions? Of course you do! Here are some references and further reading from around the web:

10 Facts about Pseudoscorpions. Fantastic blog post by arachnologist Chris Buddle, who also created this great photographic key to the pseudoscorpions of Canada.

Comstock JH (1912). THE SPIDER BOOK: a manual for the study of the spiders and their near relatives, the scorpions, pseudoscorpions, whip-scorpions, harvestmen, and other members of the class Arachnida, found in America north of Mexico, with analytical keys for their classification and popular accounts of their habits. Doubleday, Page & Company. (Available from the Biodiversity Heritage Library, with wonderful illustrations)

Harvey MS (2013). Pseudoscorpions of the World, version 3.0. Western Australian Museum, Perth.

Pseudoscorpions page on the Massey University Guide to New Zealand Soil Invertebrates website. *Includes photos of pseudoscorpions’ silk retreats!

Pseudoscorpions page on the Encyclopedia of Life.

The order of the Pseudoscorpiones. Nice summary of pseudoscorpion biology by F. Schramm, with lots of photos and scholarly references.

Zeh DW & Zeh JA (1992). On the function of harlequin beetle-riding in the pseudoscorpion, Cordylochernes scorpioides (Pseudoscorpionida: Chernetidae). Journal of Arachnology, 47-51.