UPDATE (Oct. 2017): We have just launched a new community science and public education initiative called Recluse or Not? This is a collaboration with Eleanor Spicer Rice and Matt Bertone that will allow us to obtain information about where people are finding recluse spiders inside and outside their native range in North America and help people to learn more about recluse spiders and how to identify them. Please check out the project page here for more details, and send us your photos of suspected recluse spiders on twitter! If you are not on twitter, please feel free to email me (you can find my contact information on the “about me” page).

This post addresses one of the most common spider identification questions in North America (north of Mexico): is it a brown recluse?*

A female brown recluse, Loxosceles reclusa. Photo: Alex Wild, used with permission.

The brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) is arguably the most feared and most misunderstood spider species in North America. So, here we will find out how to tell if a spider is not a brown recluse. But before we do, it’s important to note that even if you do find a brown recluse, it’s not that big a deal.

Arachnologist Rick Vetter is an expert on the brown recluse spider who has done a ton of research on where they are (and aren’t) and how dangerous they really are (hint: not as dangerous as you think), as well as spending a lot of time dispelling myths and misconceptions held by both the public and the medical community. His website is full of excellent resources, and is the source of most of the information here. I encourage you to peruse his website and the articles linked in this post yourself, but I will highlight a few of the more compelling reasons that the brown recluse hysteria is unwarranted.

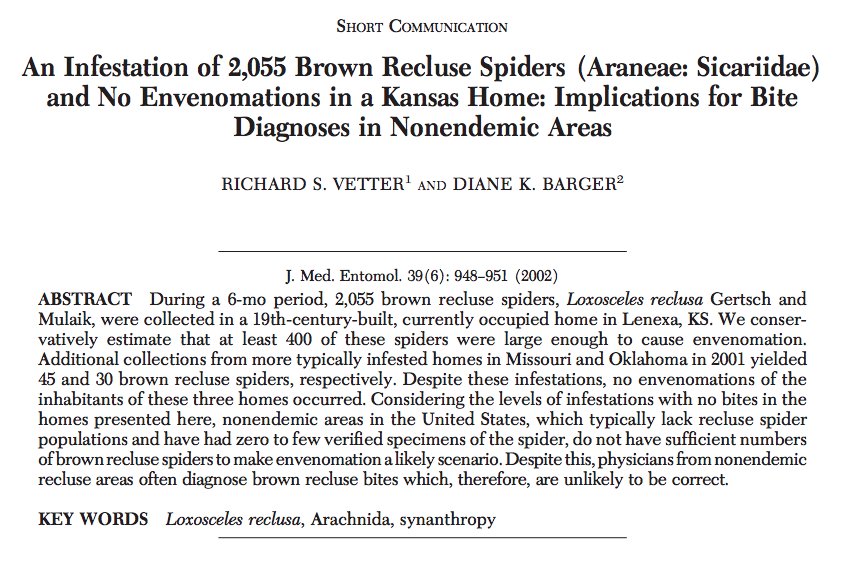

A family lived in a house full of brown recluses (more than 2000 of them!) for half a year and not a single bite occurred. Even in places where brown recluses are common, bites are very rare. Of those rare bites the vast majority of bites can be effectively treated with RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation) without any dire consequences. The small percentage of bites that are very serious are the ones that get all the attention in both the medical literature and the media, which has led to the misconception that recluse bites are always severe, require hospitalization, result in extensive scarring, and so on. Furthermore, misdiagnoses of all manner of other (more serious) conditions as brown recluse bites are rampant throughout North America (even in areas where the spiders do not occur), adding fuel to the already raging fire.

Now that all that’s out of the way, here is a series of questions to determine if a spider is NOT a brown recluse**. (Some of these may seem silly, but many of the spiders below that are not brown recluses are regularly misidentified as brown recluses by non-experts. Many people aren’t aware just how many different kinds of spiders there are, and for some, seeing brown, any marking vaguely reminiscent of a violin, and 8 legs is enough to conclude that a creature as a brown recluse.)

For those who want to skip the fine print, if the answer to question 1a or 1b is “yes”, it’s probably not a brown recluse. If the answer to any one of the remaining questions is “yes”, it’s definitely not a brown recluse.

1a. Are you in Canada (or Alaska)?

The range of the brown recluse spider does not extend into Canada. If you are in Canada, you are extremely unlikely to encounter a brown recluse spider. (Also see notes under 1b.)

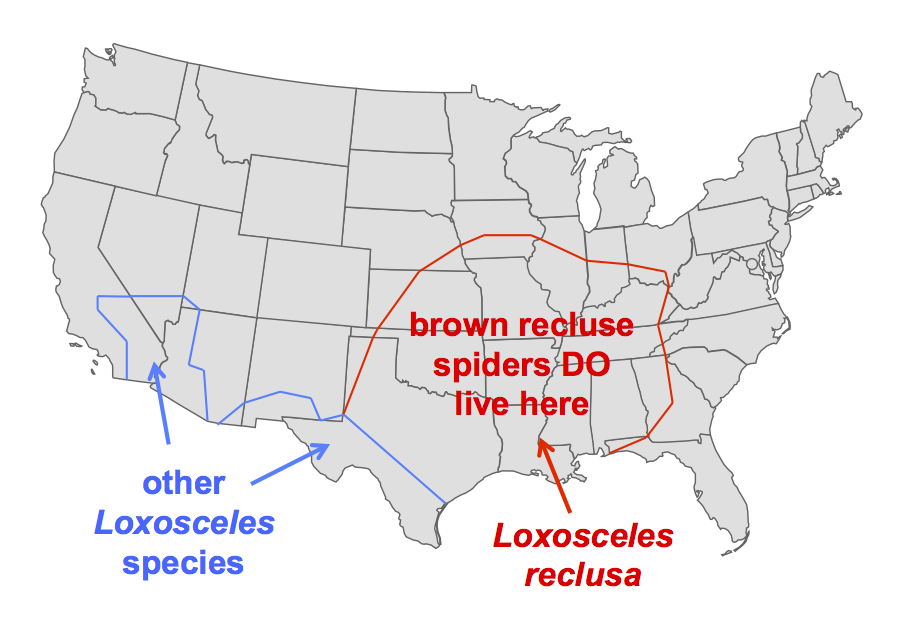

1b. Are you in a state outside of the range of the brown recluse?

Above is a map of the known ranges of all of the species in the genus Loxosceles in North America. If you are anywhere outside the red-outlined region, you are very unlikely to encounter a brown recluse.

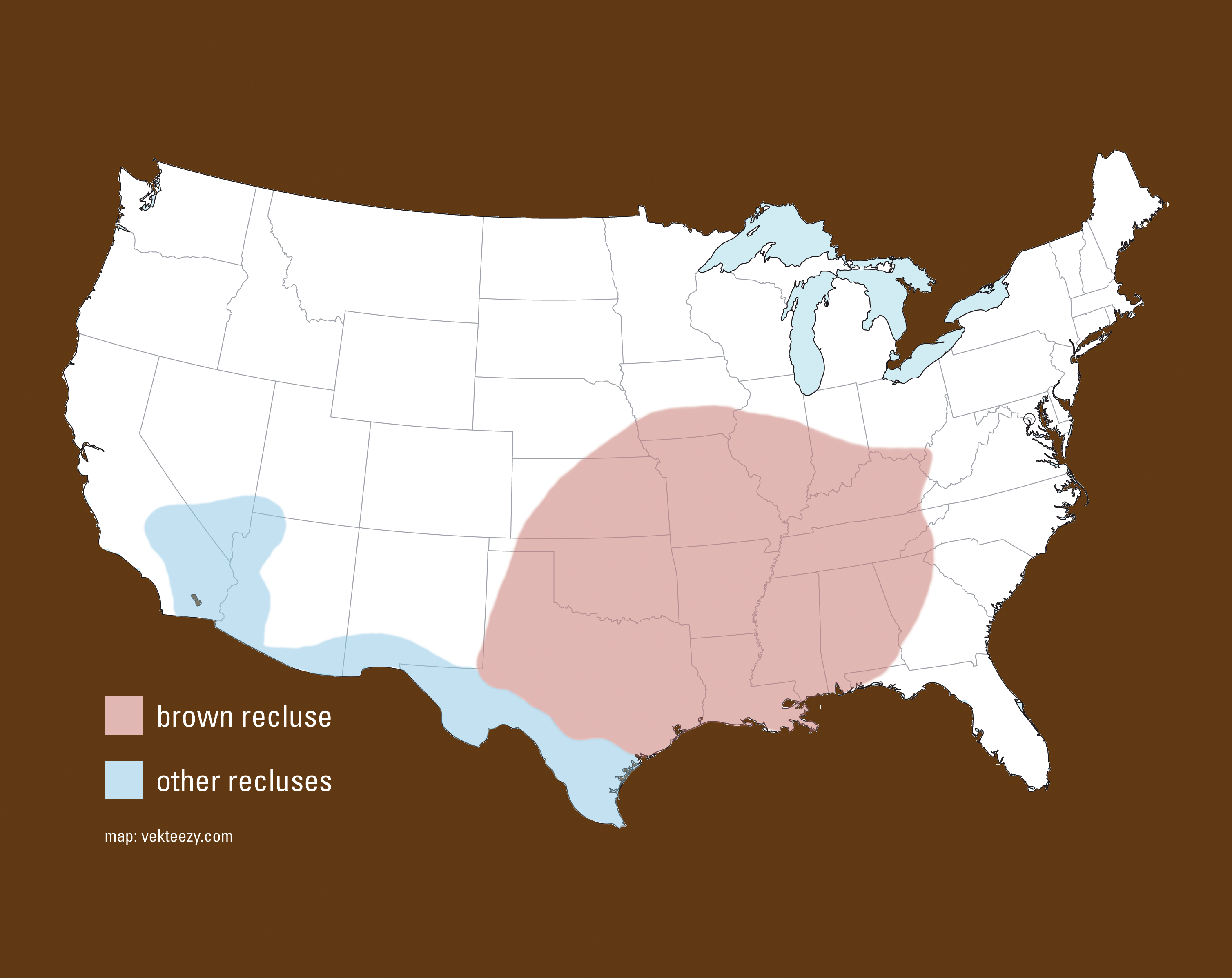

[update 2021] Below is an updated range map based on the latest data, made by Matt Bertone. For more information about recluse spiders, check out our Recluse or Not? page.

Brown recluses are occasionally found outside this range – sometimes they hitch a ride with people moving around the country (in boxes that have been stored in basements, for example). But even in these cases they will typically remain in the building into which they are introduced because they are very poor dispersers. Just because one or a few brown recluse spiders have been found in a new area does not mean that their range has expanded or that they are abundant there. (Note: A brown recluse spider bite diagnosis in an area outside their range does NOT mean that brown recluse spiders have been found there. Many doctors erroneously diagnose spider bites in the absence of any evidence, namely a spider that has been identified as the culprit.)

Brown recluses are occasionally found outside this range – sometimes they hitch a ride with people moving around the country (in boxes that have been stored in basements, for example). But even in these cases they will typically remain in the building into which they are introduced because they are very poor dispersers. Just because one or a few brown recluse spiders have been found in a new area does not mean that their range has expanded or that they are abundant there. (Note: A brown recluse spider bite diagnosis in an area outside their range does NOT mean that brown recluse spiders have been found there. Many doctors erroneously diagnose spider bites in the absence of any evidence, namely a spider that has been identified as the culprit.)

2. Is it on a web out in the open?

Some brown web-building spiders that are not brown recluses. Clockwise from top left: common garden spider (Araneus diadematus) on orb-web, dome-web spider male (Neriene radiata) false widow spider (Steatoda grossa) on cobweb giant house spider (Eratigena atrica) on funnel-shaped sheet web. Photos: Sean McCann.

If you find a brown spider on a web out in the open, it is not a brown recluse. Unlike the various brown web-building spiders shown above, each with their different types of web, brown recluse spiders do not use silk for prey capture. They do build small irregular silk retreats in which they hide during the day. These retreats are made low to the ground and out of sight in cracks and crevices or under objects like rocks.

Update (8/06/2015): I should mention that house spiders in the family Agelenidae are probably the most likely spiders to be mistaken for brown recluses in Canada. While females will usually be found on their webs, males are often found out and about when searching for females. They all look pretty similar to the one pictured below, but see this post for more information house spiders and hobo spiders.

Female giant house spider (Eratigena atrica – formerly Tegenaria duellica). These spiders are often mistaken for recluses, but note the pattern on the abdomen. Photo: Sean McCann.

3. Does it have stripy or spiky legs, or more than one colour on its abdomen?

If you find a spider that has stripes or large spines on its legs, it is not a brown recluse. If it has a patterned abdomen, it is not a brown recluse.

Stripy legs with large spines + patterned abdomen = not a brown recluse. Photo: Sean McCann.

Brown recluses have plain brown abdomens and plain brown legs with fine hair but no large spines.

4. Does it have extremely long and skinny legs?

Cellar spider, Pholcus phalangiodes (family Pholcidae). The dark spot on the cephalothorax looks a bit like a violin, but do not be fooled. This is not a brown recluse. Photo: Sean McCann

If it has extremely long skinny legs like the spider in the image above, it is a cellar spider (or daddy-longlegs), not a brown recluse. Despite looking very dissimilar to brown recluses, these spiders are often mistaken for brown recluses because of the “violin” mark on the back. Having a violin-shaped marking is not, by itself, a good way to determine if a spider is a brown recluse.

4. Is it really big?

Brown recluses are not huge spiders. If its body length (not including legs) is more than 0.5 inches or about 1.25 cm, it’s definitely not a brown recluse.

5. Does it have 8 eyes?

This is the dead giveaway, provided you are close enough to the spider to count its eyes. If it has 8 eyes (like most spiders), it is not a brown recluse. Below are some 8-eyed spiders that are sometimes mistaken for brown recluses.

Fishing spider (family Pisauridae) actually a close relative of fishing spiders in the family Trechaleidae, with 8 eyes. Also see: stripy, spiky legs. Photo: Sean McCann.

A wolf spider (family Lycosidae). Wolf spiders have 8 eyes and spines on the legs. Photo: Sean McCann.

A sac spider (family Clubionidae) A ground spider (family Gnaphosidae, genus Drassodes). It looks a bit like a brown recluse, but again, has 8 eyes, some larger spines on the legs, and a dark stripe on the abdomen. Photo: Sean McCann.

Huntsman spider (family Sparassidae). These spiders are fairly frequently mistaken for brown recluses. Note the 8 eyes in 2 rows, and spines and darker dots on the legs and abdomen. Photo: Sean McCann.

Update (12/06/2015): Another 8-eyed spider that can easily be mistaken for a brown recluse (and is common in the southern states) is the male southern house spider. It has a similar violin-like marking on the back, but several other features that distinguish it from brown recluses. The 8 eyes are all tightly clumped together, it has conspicuous spines on the legs, and its pedipalps (the two small leg-like appendages at the very front end of the spider) are extremely long and stick straight out in front of its face (compare to a male brown recluse spider here).

Male southern house spider (Kukulcania hibernalis). Photo: Sam Heck, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Some other spiders that are not brown recluses, like the woodlouse hunter Dysdera crocata, also only have only 6 eyes, but they are arranged differently (not to mention D. crocata is red or pinkish or orangish in colour, not brown).

Female woodlouse hunter, Dysdera crocata. Her 6 eyes are all in a tight bunch in the centre of the cephalothorax, and her massive fangs are much larger than those of a brown recluse. Also, these spiders are not brown. Photo: Sean McCann.

Brown recluses only have 6 eyes, arranged in 3 pairs.

This is a brown recluse. It has only six eyes. Also note the fine hairs on the legs, but no spines, and the plain brown abdomen. Photo: Alex Wild, used with permission.

If you answered no to all those questions (or all but questions 1a and 1b and you’re really lucky!) AND the spider looks just like the one in the image above, then you’ve found a brown recluse. If not, then it’s another kind of spider that is totally harmless. (The only other medically significant spiders in North America are black widows). Either way, please remain calm. Spiders are not out to get you, and will leave you alone if you leave them alone. Here are some tips for avoiding brown recluse bites if you do live within their range. Still not sure about any of this? Please feel free to tweet at me (I’m @Cataranea on twitter) or comment here if you have any questions and I’ll be happy to try to answer them.

*I’ve also started answering this question on twitter with the hashtag #notabrownrecluse. This campaign, with the goal of educating people about the brown recluse spider, is a blatant ripoff of inspired by wildlife biologist David Steen (he’s @AlongsideWild on twitter), who tweets snake identifications using the hashtags #NotACottonmouth and #NotACopperhead. For more about his awesome twitter outreach, check out this excellent article: ‘This snake scientist is the best biologist on twitter‘.

**This guide is based on the following resources:

Vetter, Rick. (1999). Identifying and Misidentifying the Brown Recluse Spider. Dermatology Online Journal, 5(2). link

Vetter, Rick. (2009). How to Identify and Misidentify a Brown Recluse Spider. Web Resource. link