All the information that follows is from Rainer Foelix’s excellent book Biology of Spiders. Photos used with permission from Sean McCann.

Here I will provide a brief orientation to the spiders that I hope will help place future posts that feature spiders in different suborders, orders and families. I will try to add more detailed taxonomy information as I go along. Also, I hope this post will help me to remember some basic information that I am always re-learning (never again will I look up orthognath vs. labidognath!).

There are about 40,000 more than 44,000 identified species of spiders in 110 112 families* (I hope that someday I will have posts highlighting every family!).

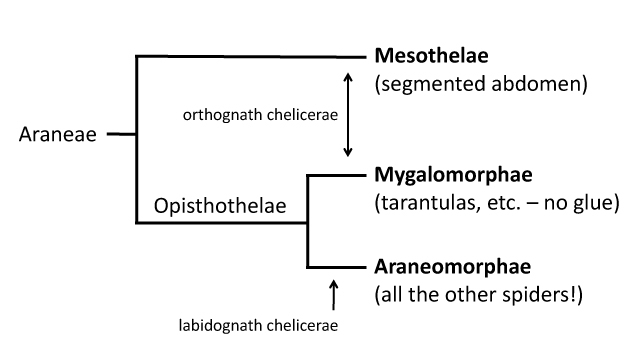

The order Araneae includes all the spiders. There are three suborders:

The most ‘primitive’ (phylogenetically oldest) spiders are in the suborder Mesothelae. They have segmented abdomens like other arthropods, and unlike the rest of the spiders. There is only one family in the Mesothelae, the Liphistiidae. I don’t really know anything else about them at this point (I will come back to them in the future).

The rest of the spiders are in the Opisthothelae, which contains the two other suborders, the Mygalomorphae and the Araneomorphae.

Both the Mesothelae and the mygalomorphs have orthognath chelicerae. Spider chelicerae are a large pair of mouthparts tipped with articulated fangs through which venom is injected into prey. Orthognath chelicerae work in parallel. Make ‘air quotes’ with your first two fingers – like that.

The majority of species in the Mygalomorphae are tarantulas, in the family Theraphosidae (in French, a tarantula is called a ‘mygale’, which makes this easy to remember ever since I spent some time in French Guiana).

Female Theraphosa blondi (Theraphosidae) in French Guiana.

There are several other less well-known families in the Mygalomorphae that I will get to in later posts. Mygalomorphs can produce silk, but most don’t build webs; they lack the pyrifrom silk glands that that araneomorphs use to cement their silk threads together or to a substrate.

Araneomorphs have labidognath (opposing) chelicerae. Touch your thumb and forefinger together repeatedly in pincer-like fashion, so. The Aranaeomorphae includes all the ‘usual’ non-tarantula spiders you might run into, including families such as the

Araneae (orb-web spiders),

Salticidae (jumping spiders),

A gorgeous Salticid. Check out those brightly coloured labidognath chelicerae! The red bits are the opposing articulating fangs.

Thomisidae (crab spiders),

Lycosidae (wolf spiders),

A female Lycosid carrying her spiderlings on her abdomen. Some spiders have highly developed brood care!

Pholcidae (cellar spiders),

A female cellar spider, Pholcus phalangiodes (Pholcidae) carrying her egg sac. I grew up calling these spiders daddy long legs, but that name is also sometimes used to refer to harvestmen (order Opiliones), which are non-spider arachnids.

Theridiidae (the combfooted spiders, also known as cobweb or tangle-web weavers),

Agelenidae (funnel-web weavers),

Female hobo spider, Tegenaria agrestis (Agelenidae). Her close relatives T. domestica and T. duellica are often found in homes.

and lots of other less common/well-known ones that I intend to make posts about in due time. Although some of them don’t build webs at all, they all produce silk draglines that can be anchored to a substrate (often useful as a sort of ‘safety line’).

To sum up, the relationships and basic differences between the three suborders look like this:

For more about the phylogenetic relationships among the Araneae see the tree of life page.

UPDATE: I learned this morning that the in the latest phylogenies Opisthothelae is considered a suborder, with Mygalomorphae and Araneomorphae as infraorders.

*UPDATE 2: Thanks to Chris Buddle for pointing me to the latest information at the World Spider Catalog!

Great post!! Nice to see ‘spider bytes’ off to such a great start. Btw, the estimate of total # of known spider species is up to over 44,000 –> see http://research.amnh.org/iz/spiders/catalog/COUNTS.html

Thanks Chris! I have updated the information accordingly!

Pingback: Spider survives 14 days in refrigerator | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: The bridal veil: how spiders tie the knot | spiderbytesdotorg

Pingback: The “Mega Spider” with an Identity Crisis | Zoom Zoo

Pingback: Spider Silk Parachutists | emilykarn

Pingback: Meet the Mygalomorphae! | spiderbytesdotorg

Pingback: Wolf Spider! | Splendour Awaits

Pingback: Bolas spiders: masters of deception | spiderbytes