Last week a colleague of mine found a tiny spider we didn’t recognize in the biology building at UTSC. We regularly find common house-dwelling spiders in and around the buildings on campus (most often false widows, Steatoda grossa triangulosa). But this spider was different from the ones we usually find in the building – tiny (only a couple of millimetres long), pale in colour, and a very fast runner! I brought it home and asked Sean to take some photos of it, and we soon realized it was a member of the fascinating family Oecobiidae. [note: this paragraph was revised on 7 Dec. 2015]

Oecobius sp. from Scarborough, Ontario. Photo: Sean McCann (used with permission)

The name Oecobiidae comes from the Greek words oikos (οικος), meaning “house” and bios (βιος), meaning “living”. A name that means “living in the house” is highly appropriate for these synanthropic spiders that are commonly found in human dwellings. The spider we found is most likely one of two species that have a worldwide distribution and can be found in southeastern Canada: Oecobius cellariorium (cellariorium means, unsurprisingly, “of the cellar” in Latin) and Oecobius navus (navus means active or busy, which these little spiders certainly are!).

Oecobiid next to its sheetweb. Photo: Mark Yokoyama, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Despite their very appropriate scientific names, non-Latin and Greek speakers have come up with a variety of fun common names for members of this family. These include wall spiders, baseboard spiders, stucco spiders, starlegged spiders, disc web spiders, and dwarf round-headed spiders. The official common name for the family is “flatmesh weavers” (at least in North America, according to the American Arachnological Society) because of the flat webs they build.

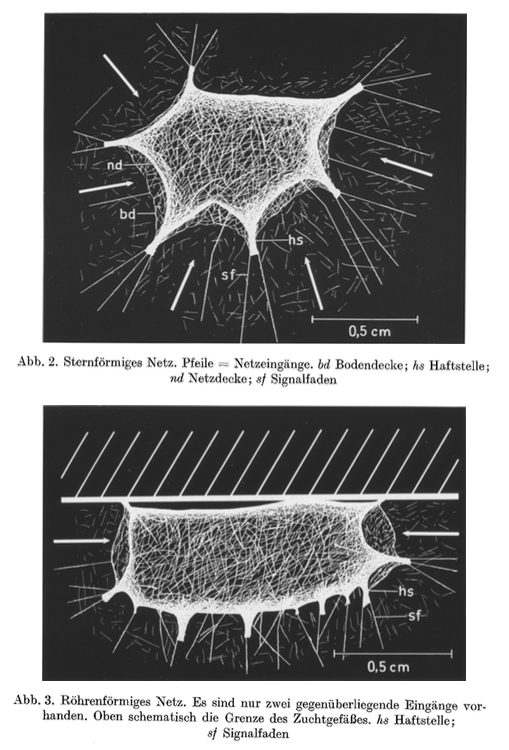

Figures 2 and 3 from Glatz 1969, showing the two kinds of webs built by Oecobius navus (previously called Oecobius annulipes). The first is a “star-shaped” web with an upper and lower sheet surrounded by radiating silk lines. These threads allow the spider sitting on the lower sheet to detect vibrations produced by prey. When the spider detects prey outside its web it can rush out in any direction to capture it. The second type of web is similar, but the upper and lower sheets form a tube, with only two entrances.

I quite like the name starlegged spiders for oecobiids though, because it so aptly describes one of the very distinctive characteristics of spiders in this family. Unlike most spiders, which have the first two pairs of legs pointing forward and the last two pointing backward (an exception is the family Segestriidae, which have the first three pairs pointing forward), oecobiids have all 8 legs sticking more or less straight out from their bodies, in a somewhat starburst-like fashion.

Oecobius sp. (male). In addition to being “star-legged”, oecobiids have their 8 eyes arranged in a characteristic cluster in the centre of a circular cephalothorax. Photo: Sean McCann

The defining characteristic of oecobiids, however, is the extraordinary anal tubercle (that’s exactly how it’s described in this paper, and I assure you it is entirely appropriate). Seriously, these tiny spiders have the most incredible hairy butts! Ahem. Fringed anal tubercles, I mean. Let me explain.

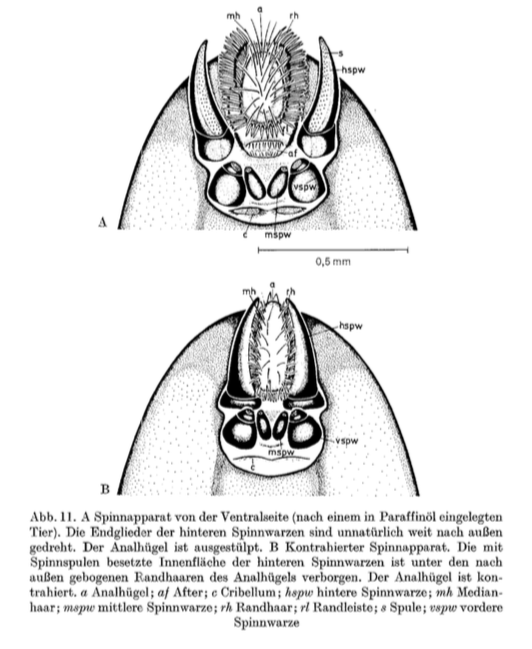

The North American oecobiids are cribellate spiders. What this means is that the spider is equipped with a cribellum (a special silk spinning organ covered with thousands of tiny spigots) near the spinnerets and a calamistrum (a specialized row of bristles) on each of the fourth legs. The calamistrum is used to comb out fine strands of cribellar silk into sheets with a fuzzy texture. The stickiness of this silk comes from its physical structure, as opposed to the glue used by ecribellate (non-cribellate) spiders to make their capture silk sticky. Anyway, instead of combing silk out of the cribellum with the calamistrum like regular cribellate spiders, oecobiids have their own fancy way of doing things. They use the fringe of hairs on their jointed anal tubercles to comb silk directly from arrays of spigots on a pair of enlarged spinnerets.

Figure 11 from Glatz 1969, showing the extraordinary fringed anal tubercle and spinning apparatus. The long posterior lateral spinnerets (labelled hspw) are covered with spigots (s). The outer fringe of hairs (rh) on the anal tubercle comb silk out of the spinnerets. The anal tubercle is also equipped with sensory hairs (mh) that are used to detect prey movement via vibrations through the silk threads.

This unusual set-up enables oecobiids to produce a sheet of sticky silk without using their legs, which is important for their unusual method of prey capture. Many spiders use their last pair of legs to pull sticky silk out of their spinnerets and throw it onto their prey. Oecobiids, instead, run around and around their prey in circles as they spew out ribbons of silk from their feathery butts. Once the victim (often an ant) is fully encircled and stuck to the substrate, the spider bites it. Here is a video of the behaviour. (Video* by Ahmet Özkan, used with permission.)

As you can see in the video, the spider does occasionally use its last pair of legs while wrapping the ant with silk, but the anal tubercle/spinneret combo does most of the work. Female and juveniles of Oecobius navus can produce cribellar silk, but adult males have a reduced cribellum and don’t have a calamistrum at all. Another oecobiid genus, Uroctea, used to be placed in its own family, the Urocteidae, because they are ecribellate (lacking the cribellum and calamistrum).

Uroctea durandi, one of the ecribelleate oecobiids. Photo: Siga, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Early work on spiders in the genus Oecobius suggested that they were ant-specialists, but more recent research has shown that they eat a variety of prey types. However, different populations of a single species seem to specialize to some extent on whatever type of prey is most locally abundant. In Portugal, a population of Oecobius navus preys mainly on ants, but another population in Uruguay eats mostly flies.

Male (right) and female (left) Oecobius sp. Photo: Allan Lance (used with permission). Check out more of Allan’s photos of oecobiids here.

Reproductive behaviour has only been well documented in Oecobius navus. The male spins a tubular silk mating web on top of the female’s retreat and tries to entice her to join him inside. Copulation only occurs if she enters the male’s web, and sometimes the female will cannibalize the male during or after mating. Females are not caring mothers in this species – they spin several egg sacs that each contain only 3 to 10 eggs and then abandon them.

Oecobius sp. from Scarborough. Photo: Sean McCann

Now that you know all about oecobiids, keep your eyes out for them! They live all over the world, and often on the walls and ceilings of houses. You never know – there might be one in the room with you right now!

This photo of an Oecobius sp. is one Sean dug up from his archives. We had found the spider in our old lab at SFU in BC, and did not identify it at the time. When Sean showed me the photo recently, and I started trying to ID it, I took a look at the checklist of BC spiders to get an idea of which species it might be. I didn’t see any oecobiids on the list, so I emailed the author, Robb Bennett, and it turns out that this photo is the first record of the family for British Columbia.

*For another cool oecobiid video with a surprise ending, click here.

References

Adams, R. J. (2014). Field Guide to the Spiders of California and the Pacific Coast States (Vol. 108). Univ of California Press.

Glatz, L. (1967). Zur biologie und morphologie von Oecobius annulipes lucas (Araneae, Oecobiidae). Zeitschrift für Morphologie der Tiere, 61(2), 185-214.

Líznarová, E., Sentenská, L., García, L. F., Pekár, S., & Viera, C. (2013). Local trophic specialisation in a cosmopolitan spider (Araneae). Zoology, 116(1), 20-26.

Shear, W. A. (1970). The spider family Oecobiidae in North America, Mexico, and the West Indies. Harvard Univ Mus Compar Zool Bull.

Great blog! Thanks for sharing.

Nice post Catherine! Cool spiders!

Love this – I learn so many things. Jumping spider in the vimeo?

Yes, a jumping spider! Poor oecobiid!

Pingback: Spiderday (#23) – Happy Holidays | Arthropod Ecology

Pingback: Morsels For The Mind – 18/12/2015 › Six Incredible Things Before Breakfast